By: James Masucci

Have you ever juggled? You can’t just focus on one ball; you must keep an eye on the whole bunch of them. Seems like you can never spend enough time on one because the next one is always falling. Well, this seems to be my experience with putting up my honey house. I thought I’d share these experiences so you can learn from them. I am NOT saying that I know what I’m doing or going about this the right way. But, perhaps by sharing my experience and thought processes, you can have an idea of what to expect and figure out a better way.

It all starts with a location. A suitable site, however, is dependent on how I am going to use the facility. How big MAY I grow and what MAY I use this for? “May” is critical here. I don’t want to make a huge investment on something I will outgrow in five years. Then again, I don’t want to build something I will never come close to occupying. Things to think about: How much equipment do you plan on storing? Will there be any fleet vehicles to store? Will this need to be an inspected facility? Will you be moving things by hand, pallet jack, or forklift? Will you have a full extraction line?

Many of these questions relate to how big of a building you need. However, the site is just as important. If you are large enough, you will be getting freight shipments. Will there be room for delivery trucks? If there are fleet vehicles, are they stored in a building or will you fence in the property? Will the garage and storage sheds be part of, or separate from, the honey house? Answers to these questions tell you whether you need one acre or five acres.

For me, I want a single building that will serve as a garage, a honey house, and storage facility. The garage will be a walled off section for my bee truck. I will have a second room for a kitchen/bottling facility that will pass inspection (though I am not big enough for that, yet). It will have a bathroom/shower/laundry room to help me pass inspections as well as eliminate my wife handling bee garments in our personal laundry. Lastly, it will have plenty of space for extracting and storage. I want to park my truck indoors because it will be unattended for long periods of time. I need enough space for delivery trucks and random equipment. I don’t plan on having bees on this property, because I don’t want a feeding frenzy when I’m bringing in honey supers, but I still don’t want to be right next to neighbors. I know from experience that bees and neighbors don’t always mix. So, I went looking for a couple of rural acres, keeping in mind that I need water, sewer/septic, and electricity. Living in the suburbs of St. Louis, land is not cheap. The farther away I go, the cheaper the land gets, but the farther I need to travel to my “base camp” every day. My strategy was to be within 15 minutes of one of my yards. Then, once I have my “base camp” established, I can expand around it so that eventually, it is in the middle of all my bees rather than the outskirts.

First look; an old gas station. Close, but not right. Floor space is not an open design, no place for deliveries (including supers) and the floor was not very solid.

The first place I looked at was an old gas station (from the ‘50s) that had the gas tanks removed and had been on the market for five to 10 years (see picture). It had water, sewer, and electricity. It also had an old cold room which I could use to store boxes (prevent wax moths). However, it was not built on a slab which would prevent me from ever using a forklift. There was no place to park my truck and no delivery access (garage door) on the building. John Miller told me, “think Walmart, open building, one floor, easy access to everything”. It could work but wasn’t right for me. Besides, it was 25 minutes beyond my farthest yard and not in a great area.

The first place I looked at was an old gas station (from the ‘50s) that had the gas tanks removed and had been on the market for five to 10 years (see picture). It had water, sewer, and electricity. It also had an old cold room which I could use to store boxes (prevent wax moths). However, it was not built on a slab which would prevent me from ever using a forklift. There was no place to park my truck and no delivery access (garage door) on the building. John Miller told me, “think Walmart, open building, one floor, easy access to everything”. It could work but wasn’t right for me. Besides, it was 25 minutes beyond my farthest yard and not in a great area.

Not a bad property. Relatively flat and only 5 minutes from my closest bee yard. I would need to bring in electric, dig a well, and put in a septic system. But $120,000? No way

The second spot I looked at was seven acres smack in the middle of all my yards. Perfect location, until I went to see it. $80,000 for a steep hillside that didn’t have a single place for me to build. No water, no sewer, no electricity, no deal. The third location I found while driving around. “3 acres for sale” in a perfect location. I stopped on the road and called the realtor. “…you mean the commercial property on the outage road? That’s $3 a square foot”. “What?” I said, “you want $120,000 an acre?”. His reply….”you are obviously new to looking at commercial property”. Oh yes I was. At this point, the gas station was looking better. I had a couple more of those conversations which helped me narrow down where I needed to look, the type of land I was looking for (agricultural) and what I should expect to pay. And the search continued.

This is it! The top is relatively flat. Ten minutes from my closest bee yard. Sewer, water, and electric on the property and a good location for someone to build a nice home when we are finished with it. AND, it comes with a tire swing.

One Thursday night, we had some friends over for dinner and, as usual, they asked “how are the bees?” After hearing about our land search, one of our friends told me how he constantly searches the MLS listings because he is looking for a place in the general area I’m looking and offered to pass along anything that he finds. That Sunday morning, I found an e-mail from him in my inbox. A two-acre plot that used to have a trailer on it (so it was relatively flat), that had water, sewer, and electricity on site. Water, sewer, and electricity alone are worth a lot of money. I had to visit a beeyard out there, so I stopped by….10 minutes from the yard. I immediately envisioned where I would put the building. Plenty of space for the building and for delivery trucks. I called my wife as I as going to my next yard and we agreed to see it when I got back home. As we drove into the yard around noon, we met the owners. Had a great conversation. My wife liked it. By five o’clock, the property was ours with the contingency that the county would allow for the building that I wanted to put up. They did. It’s ours.

What gave us the confidence in this property to buy it the same day we saw it (besides that there were two other offers that day…)? First was location. The property is five minutes from a town that is on the edge of the urban sprawl that’s happening in our area. When I retire from beekeeping in 10-15 years, we think we will more than get our money back for the property. Second is location (location, location, location, right). The property is 10 minutes from the out-yard closest to my house and 15 minutes from the next one in line. Fairly convenient from my beeyards even though it is 30 minutes from my house. Third is location. It’s in a great area to expand my yards into. It will be an excellent centralized location for my bee operation. Fourth, it had all the utilities that I will need. Sewer, water, and electricity are on site. I just need to tap in. Fifth, it has sufficient space and a couple great building sites (more on that in my next article) for the building I want to put up and any extra storage that I may need in the future. Sixth, the county that it is in is Ag friendly and business friendly making code compliance relatively easy and the building department very helpful. Seventh is neighbors, or lack thereof. To the South of the building site, I own 100 feet of lawn and 200 feet of woods. Beyond my woods are more woods, then pastureland. To the west is a two acre empty plot of woods and next to that is a non-retail business. To the north is a house at least 100 yards away with a tree line in between. To the east is the only real neighbor and between the building site and them is a thick tree line.

So now I have my land. The next step is the preparation for putting up the building. Determining size, developing a floor plan , getting appropriate permits, and finding people to do the work that I don’t how to do. But that’s for the next article.

Click here to go directly to Part 4 – A Shout Out to My Friends

Click here to go directly to Part 6 – Getting Ready to Build

]]>By: James Masucci

Have you ever juggled? You can’t just focus on one ball; you must keep an eye on the whole bunch of them. Seems like you can never spend enough time on one because the next one is always falling. Well, this seems to be my experience with putting up my honey house. I thought I’d share these experiences so you can learn from them. I am NOT saying that I know what I’m doing or going about this the right way. But, perhaps by sharing my experience and thought processes, you can have an idea of what to expect and figure out a better way.

It all starts with a location. A suitable site, however, is dependent on how I am going to use the facility. How big MAY I grow and what MAY I use this for? “May” is critical here. I don’t want to make a huge investment on something I will outgrow in five years. Then again, I don’t want to build something I will never come close to occupying. Things to think about: How much equipment do you plan on storing? Will there be any fleet vehicles to store? Will this need to be an inspected facility? Will you be moving things by hand, pallet jack, or forklift? Will you have a full extraction line?

Many of these questions relate to how big of a building you need. However, the site is just as important. If you are large enough, you will be getting freight shipments. Will there be room for delivery trucks? If there are fleet vehicles, are they stored in a building or will you fence in the property? Will the garage and storage sheds be part of, or separate from, the honey house? Answers to these questions tell you whether you need one acre or five acres.

For me, I want a single building that will serve as a garage, a honey house, and storage facility. The garage will be a walled off section for my bee truck. I will have a second room for a kitchen/bottling facility that will pass inspection (though I am not big enough for that, yet). It will have a bathroom/shower/laundry room to help me pass inspections as well as eliminate my wife handling bee garments in our personal laundry. Lastly, it will have plenty of space for extracting and storage. I want to park my truck indoors because it will be unattended for long periods of time. I need enough space for delivery trucks and random equipment. I don’t plan on having bees on this property, because I don’t want a feeding frenzy when I’m bringing in honey supers, but I still don’t want to be right next to neighbors. I know from experience that bees and neighbors don’t always mix. So, I went looking for a couple of rural acres, keeping in mind that I need water, sewer/septic, and electricity. Living in the suburbs of St. Louis, land is not cheap. The farther away I go, the cheaper the land gets, but the farther I need to travel to my “base camp” every day. My strategy was to be within 15 minutes of one of my yards. Then, once I have my “base camp” established, I can expand around it so that eventually, it is in the middle of all my bees rather than the outskirts.

First look; an old gas station. Close, but not right. Floor space is not an open design, no place for deliveries (including supers) and the floor was not very solid.

The first place I looked at was an old gas station (from the ‘50s) that had the gas tanks removed and had been on the market for five to 10 years (see picture). It had water, sewer, and electricity. It also had an old cold room which I could use to store boxes (prevent wax moths). However, it was not built on a slab which would prevent me from ever using a forklift. There was no place to park my truck and no delivery access (garage door) on the building. John Miller told me, “think Walmart, open building, one floor, easy access to everything”. It could work but wasn’t right for me. Besides, it was 25 minutes beyond my farthest yard and not in a great area.

Not a bad property. Relatively flat and only 5 minutes from my closest bee yard. I would need to bring in electric, dig a well, and put in a septic system. But $120,000? No way.

The second spot I looked at was seven acres smack in the middle of all my yards. Perfect location, until I went to see it. $80,000 for a steep hillside that didn’t have a single place for me to build. No water, no sewer, no electricity, no deal. The third location I found while driving around. “3 acres for sale” in a perfect location. I stopped on the road and called the realtor. “…you mean the commercial property on the outage road? That’s $3 a square foot”. “What?” I said, “you want $120,000 an acre?” His reply….”you are obviously new to looking at commercial property”. Oh yes I was. At this point, the gas station was looking better. I had a couple more of those conversations which helped me narrow down where I needed to look, the type of land I was looking for (agricultural) and what I should expect to pay. And the search continued.

One Thursday night, we had some friends over for dinner and, as usual, they asked “how are the bees?” After hearing about our land search, one of our friends told me how he constantly searches the MLS listings because he is looking for a place in the general area I’m looking and offered to pass along anything that he finds. That Sunday morning, I found an e-mail from him in my inbox. A two-acre plot that used to have a trailer on it (so it was relatively flat), that had water, sewer, and electricity on site. Water, sewer, and electricity alone are worth a lot of money. I had to visit a beeyard out there, so I stopped by….10 minutes from the yard. I immediately envisioned where I would put the building. Plenty of space for the building and for delivery trucks. I called my wife as I as going to my next yard and we agreed to see it when I got back home. As we drove into the yard around noon, we met the owners. Had a great conversation. My wife liked it. By five o’clock, the property was ours with the contingency that the county would allow for the building that I wanted to put up. They did. It’s ours.

This is it! The top is relatively flat. Ten minutes from my closest bee yard. Sewer, water, and electric on the property and a good location for someone to build a nice home when we are finished with it. AND, it comes with a tire swing.

What gave us the confidence in this property to buy it the same day we saw it (besides that there were two other offers that day…)? First was location. The property is five minutes from a town that is on the edge of the urban sprawl that’s happening in our area. When I retire from beekeeping in 10-15 years, we think we will more than get our money back for the property. Second is location (location, location, location, right). The property is 10 minutes from the out-yard closest to my house and 15 minutes from the next one in line. Fairly convenient from my beeyards even though it is 30 minutes from my house. Third is location. It’s in a great area to expand my yards into. It will be an excellent centralized location for my bee operation. Fourth, it had all the utilities that I will need. Sewer, water, and electricity are on site. I just need to tap in. Fifth, it has sufficient space and a couple great building sites (more on that in my next article) for the building I want to put up and any extra storage that I may need in the future. Sixth, the county that it is in is Ag friendly and business friendly making code compliance relatively easy and the building department very helpful. Seventh is neighbors, or lack thereof. To the South of the building site, I own 100 feet of lawn and 200 feet of woods. Beyond my woods are more woods, then pastureland. To the west is a two acre empty plot of woods and next to that is a non-retail business. To the north is a house at least 100 yards away with a tree line in between. To the east is the only real neighbor and between the building site and them is a thick tree line.

So now I have my land. The next step is the preparation for putting up the building. Determining size, developing a floor plan , getting appropriate permits, and finding people to do the work that I don’t how to do. But that’s for the next article.

]]>

By: Becky Masterman & Bridget Mendel

What is propolis? Etymologically, propolis derives from the Greek for “before the city” (pro=before, polis= city or community). Entomologically, propolis is derived by bees (honey bees and stingless bees) from plant resins, mixed with beeswax and enzymes (and possibly other things) and cemented around the bees’ nest cavity.

Propolis has seemingly endless beneficial properties for humans and bees. A plebian might call it a magic potion and leave it at that. But for scientists, propolis is uniquely challenging to study. While propolis is antifungal, antiviral, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and even anticancer, it is also antistandardized. Okay we made the last word up (Lizzo says we can). But what we are getting at is that propolis has different properties and actions depending on the source of the plant resin. Components of propolis have numbered over 300 and standardizing propolis based on plant source would be needed to support repeatable results when harnessing the power of this natural, but complex substance (Sforcin 2016).

When this hive was pried open, it revealed a thick layer of propolis between the boxes. Photo credit: Judy Griesedieck

And propolis means different things to different beings:

If you are a honey bee…

Propolis is the substance you collect from the leaf buds of trees, plastering it into the cracks and crevices of your nest cavity. You use propolis as a form of social healthcare; this antimicrobial substance helps you and your sisters to stay healthy collectively. With propolis around the home, your immune system can rest up, ready to kick into high gear if needed (Simone et al. 2009, Borba et al. 2015).

If you are a stingless bee…

If you are a stingless bee, you have many uses for plant resins in the hive. Stingless bee management, or meliponiculture, is practiced for the production of honey and hive resin products, including propolis, as well as pollination (Cortopassi-Laurino et al. 2006). A recent review by Shanahan and Spivak (2021) provides insight into the complexity of resin use in this diverse and populous (over 500 described species!) group.

If you are a beekeeper…

If you are a beekeeper, propolis is why you keep a little old crowbar in your back pocket. Propolis is like cement, it stains your clothes forever, gets under your fingernails, and turns your palms orange-green-yellow. Some beekeepers have allergies to certain types of propolis. Ah, the things we tolerate for the sake of our bees.

If you are a cottonwood tree…

If you are a cottonwood tree, or a poplar tree for that matter, propolis is just a pretentious word for resin. It’s like how a very thin piece of ham is called prosciutto just because it is cured and expertly sliced?? It’s unclear if honey bees cure or otherwise tamper with the medicinal resins they collect from the leaf buds of trees, but essentially it is the same substance, give or take some enzymes. If you are a tree, you produce resin to protect yourself from insects and pathogens.

A drug developer or medicine maker…

If you are in the business of medicine making, you are acquainted with the numerous biological activities of propolis reported by researchers. Herbalists have been using propolis for wound dressing and oral health since King Nyuserre reigned Egypt (Hammad 2018). More clinical work needs to be done in order to understand and further harness the potential of propolis for human health (Silva-Carvalho et al. 2015).

Solitary bee nest made of propolis.

Photo credit: Judy Griesedieck

If you are a food scientist…

If you study food as well as eat it, you might be intrigued by the potential of a propolis extract as a food preservative. The antiviral properties of propolis have been investigated with positive results in both fruit and vegetable juices (Nigbo et al. 2021).

If you are a violin maker…

If you are a maker of violins, you’re all about the resin-derived products. Stringed instrumentalists rub pine resin (they call it rosin) onto their bow hair, to create friction across the strings when they play (bees do not collect pine resin). You also may use bee propolis in the varnish for your instruments. Furthermore, you may actually be the guy who ended up in a scientific paper describing your propolis allergy in detail (Lieberman et al. 2002).

If you are an ancient Egyptian undertaker….

If you are an undertaker in ancient Egypt, you use propolis all the time to embalm mummies. Your brother, a local doctor, uses propolis for the living; for treating wounds, gashes, and toothaches.

If you are a dentist…

Dentists should totally read this recent study that shows promise that propolis, used in a mouthwash, could help reduce gingivitis (inflammation and bleeding in gums) (Kiani et al. 2021). Propolis has been long used in toothpastes, lozenges, creams and mouthwash, but research is ongoing to understand the benefits and mechanisms of its oral health support (Khurshid et al. 2017).

If you are still reading this article…

You are now a proponent of propolis. Pro-propolis. A proprolite. A proprolitizer. Scientists are still catching up on what the bees have always known, namely that tree resins are definitely worth collecting. We’re excited to continue following the scientists dedicated to unlocking the mysteries of this stickiness, further describing how it can be used in and out of the hive.

Authors

Becky Masterman led the UMN Bee Squad from 2013-2019 and currently alternates between acting as an advisor and worker bee for the program. Bridget Mendel joined the Bee Squad in 2013 and has led the program since 2020. Photos of Becky (left) and Bridget (right) looking for their respective hives.

References

- Borba, R., Klyczek, K., Mogen, K., Spivak, M. 2015 Seasonal benefits of a natural propolis envelope to honey bee immunity and colony health. J. Exp. Biol. doi:10.1242/jeb.127324

- Cortopassi-Laurino, M., Imperatriz-Fonseca, V., Roubik, D., Dollin, A. Heard, T., Aguilar, I., Venturieri, G., Eardley, C., Noguera-Neto, P.(2006) Global meliponiculture: Challenges and opportunities PARIS: SPRINGER FRANCE Apidologie, Vol.37 (2), p.275-292

- Hammad, M. (2018) Bees and beekeeping in ancient Egypt. Journal of Association of Arab Universities for Tourism and Hospitality. Vol 15 10.21608/ jaauth.2018.47990 www.researchgate.net/publication/335839271_BEES_AND_BEEKEEPING_ IN_ANCIENT_EGYPT

- Khurshid, Z., Naseem, M., Zafar, M. S., Najeeb, S., & Zohaib, S. (2017). Propolis: A natural biomaterial for dental and oral healthcare. Journal of dental research, dental clinics, dental prospects, 11(4), 265–274. https://doi.org/10.15171/joddd.2017.046

- Kiani, S., Birang, R. and Jamshidian, N. (2021), Effect of Propolis Mouthwash on Clinical Periodontal Parameters in Patients with Gingivitis: A Double Blinded Randomized Clinical Trial. International Journal of Dental Hygiene. Accepted Author Manuscript. https://doi-org.ezp3.lib.umn.edu/10.1111/idh.12550

- Lieberman, H. Fogelman, J., Ramsay, D. Cohen, D. (2002) Allergic contact dermatitis to propolis in a violin maker, Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Volume 46, Issue 2, Supplement 1, Pages S30-S31, ISSN 0190-9622, https://doi.org/10.1067/mjd.2002.106349.

- Lizzo https://genius.com/a/lizzo-missy-elliott-team-up-for-the-tempovideo

- Ningbo Liao, Liang Sun, Dapeng Wang, Lili Chen, Jikai Wang, Xiaojuan Qi, Hexiang Zhang, Mengxuan Tang, Guoping Wu, Jiang Chen, Ronghua Zhang (2021) Antiviral properties of propolis ethanol extract against norovirus and its application in fresh juices, LWT, Volume 152, 112169, ISSN 0023- 6438, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2021.112169. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0023643821013220)

- Sforcin, J. M. (2016) Biological Properties and Therapeutic Applications of Propolis. Phytother. Res., 30: 894– 905. doi:10.1002/ptr.5605.

- Shanahan, M. and Spivak, M. (2021) Resin Use by Stingless Bees: A Review. MDPI AG Insects (Basel, Switzerland), Vol.12 (8), p.719

- Silva-Carvalho, R., Baltazar, F., & Almeida-Aguiar, C. (2015). Propolis: A Complex Natural Product with a Plethora of Biological Activities That Can Be Explored for Drug Development. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 206439-29.

- Simone M., Evans J., Spivak M. (2009) Resin collection and social immunity. Evolution 63: 3016-30222

Honey bees are interconnected within colonies, with a crowded three-dimensional space that favors constant contact. Add shared feeding and a mite that is mobile enough to connect viruses from one bee host to another, and it is safe to say that no colony member is socially distant from the whole. Fortunately, bees have a range of defenses, from molecules to mandibles, that help them reduce the spread and impacts of disease. When this fails, beekeepers can add another layer, most importantly by reducing mite levels and being overly cautious with signs of brood disease. Thanks to these defenses, honey bees are bruised but still with us and hardworking beekeepers are still providing a great service to agriculture.

One research area that has received much attention is the ability of environmental stressors, including pesticides, to reduce the defensive posture of bees and colonies against disease. Early work by Gennaro di Prisco and colleagues suggested that chemical stress directly impacts the immune responses of bees toward viral infection, a fact that was championed to explain an apparent upswing in viral impacts on bee health (“Neonicotinoid clothianidin adversely affects insect immunity and promotes replication of a viral pathogen in honey bees”. 2013. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(46), 18466-18471, https://www.pnas.org/content/110/46/18466). While mite vectors are arguably far more important for viral disease than chemical stress, determining a role for chemical stress on viral immunity has led to several important research studies. These studies are summarized in a timely review by Gyan Harwood and Adam Dolezal in the open-access journal Insects (“Pesticide–virus interactions in honey bees: Challenges and opportunities for understanding drivers of bee declines”. 2020. Viruses 12, 566. https://doi.org/10.3390/v12050566). Alongside a plea for additional research, the authors of this review make a good case for connecting the dots between chemical insults and vulnerability to viruses. Interestingly, while they describe many laboratory studies that show an increase in viral levels when bees are exposed to chemicals, such viral outbreaks have not been confirmed in colonies in the field. Why is that?

First, field experiments are far more costly and it is hard to generate the numbers of independent control and exposed colonies needed to see subtle changes in viral infections. Second, in even the most ambitious field experiments, colonies are able to collect food sources beyond those prepped with chemicals, and it is possible they are diluting pesticide intake. Weakening these two hypotheses, bees in field colonies HAVE been shown to express behavioral and longevity effects from exposure to chemicals. An alternative explanation for survival of honey bee colonies after chemical stress is resilience (the topic of my July Bee Culture article). Several recent papers suggest that this resilience starts in the bee gut.

Having done numerous lab studies with live bees, it is really hard to give them adequate ‘lab-based’ nutrition. It is quite likely that most laboratory stress assays for bees involve suboptimal nutrition. Further, as documented abundantly by May Berenbaum and colleagues at the University of Illinois, natural chemicals found in many pollen and nectar sources can themselves trigger defenses in bees that help reduce the impacts of dangerous pesticides (for example, ‘Increase in longevity and amelioration of pesticide toxicity by natural levels of dietary phytochemicals in the honey bee, Apis mellifera. 2020. PLoS ONE 15, e0243364; doi:10.1371/journalpone.0243364). The impacts of plant-based chemicals on bee health merits it’s own discussion given strong evidence that these chemicals can also reduce bee disease, but the link to pesticide tolerance is especially interesting. Certain chemicals found in pollen and nectar trigger the same detoxification enzymes bees use to dampen the impacts of pesticides. If this triggering offers protection (a phenomenon called hormesis or, informally, ‘hair of the dog’) this might lead to practical avenues of reducing chemical stress on bees. Of course, it is also possible that plant chemicals over-tax the same enzymes and other processes that are needed to smother pesticides, in which case synergies might arise to the harm of bees. Synergies between agrochemicals that lead to unexpectedly dire results for bees are known, but so far there are no identified synergies of this sort between chemicals found in bee forage and synthetic chemicals used in farming or beekeeping.

So what is the evidence that nutrition, or these plant chemicals alone, can provide real-world protection to honey bees against pesticide stress? A recent paper by Lena Barascou and colleagues shows that supplemental pollen gives some measure of protection against the pesticide sulfoxaflor (Pollen nutrition fosters honey bee tolerance to pesticides. 2020. R. Soc. Open Sci. 8: 210818. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.210818). Bees given a pollen boost had lowered mortality after both acute and chronic exposure to sulfoxaflor. After chronic exposure, bees had 2.5- and 2-fold greater survival when exposed to sulfoxaflor IF they were fed a pollen mix heavy with mustard and oak sources, or one with pollen from willow trees and other sources, respectively. Only the former pollen offered protection from an acute pesticide dose in this study. Interestingly, oak pollen is heavy with one of the plant chemicals highlighted by Berenbaum’s group as being especially important for bee detox responses. Given the different chemistries of these pollens, it is also possible that pollen as a whole can provide some protection from chemicals, i.e., a ‘better nutrition equals better resilience’ hypothesis is not ruled out.

Bees in colonies also carry abundant microbial associates in their guts and there is evidence that these associates themselves enable greater tolerance toward pesticide stress. This is important for beekeepers both because antibiotic use in hives is known to reduce microbe numbers and change their constituencies, and because several researchers and companies are developing microbial supplements (prebiotics and probiotics) purported to improve bee health. In one recent study, Brendan Daisley and colleagues tested the abilities of a common environmental bacterium to reduce the impacts of imidacloprid on fruit flies (“Neonicotinoid-induced pathogen susceptibility is mitigated by Lactobacillus plantarum immune stimulation in a Drosophila melanogaster model”. 2017. Scientific Reports, 7:2703, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-017-02806-w). As with bees, low-level chemical exposure increased disease susceptibility, but that susceptibility was offset by supplementing the insects with a single bacterial species. The authors argue that this dynamic could help bees in the field survive chemical insults and they are actively pursuing this. In support of this, researchers in the laboratory of Nancy Moran (a pioneer who has made huge discoveries in the roles and makeup of bee gut bacteria) have shown that bees given a probiotic ‘cocktail’ after antibiotic cleansing of their guts show greater resistance to bacterial disease (“Field-realistic tylosin exposure impacts honey bee microbiota and pathogen susceptibility, which Is ameliorated by native gut probiotics” 2021. Microbiology Spectrum. 9(1):e0010321. doi: 10.1128/Spectrum.00103-21. They and others have also shown interactions between these native gut bacteria and pesticides used in agriculture.

In summary, different experimental outcomes in field versus laboratory experiments require us to push for more realistic lab setups (modeled perhaps by the Barascu paper and with a ‘common’ pollen source). It is also important to invest, where possible, in more costly but more realistic experiments in the world of beehives. Finally, we are learning more and more about both the subtle harms of a range of environmental stressors, including pesticides, and potential means for reducing these impacts on bees and other key pollinators.

]]>When examining a hive, the beekeeper can tell what is going on inside by answering a few important questions. Does the colony have swarm, supersedure, or emergency queen cells? Are there empty queen cells from which a virgin queen has emerged? How many queen cells total are there, and where are they located? The beekeeper also looks to see if there are worker brood, drone brood, and the stages of this brood (egg, larvae, pupa, emerged). Are there signs of a laying worker(s) such as drone brood raised in worker cells? How large is the brood nest? Where are the frames of pollen located, and where are the brood nest pollen bands? Is honey stored in the corners of frames of the brood nest or in the super above the brood nest? Are there signs of wax moths or small hive beetles such as debris on the bottom board? How much damage exists from wax moths or small hive beetles? Are there signs of American Foulbrood, European Foulbrood, or of Varroa mites (“snott” brood, Varroa visible on drone brood, deformed wings)?

A normal colony

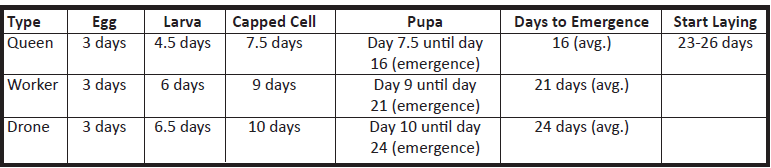

The brood development of a normal colony follows the seasonal bee-year. The colony begins building its population the latter part of December, with peak brood-rearing culminating during the nectar flow. When swarming occurs, it is usually during the nectar flow and in healthy colonies that have plenty of honey and pollen available. In the spring, worker brood follows the 1/2/4 rule that means there should be twice as many larvae as eggs, and four times as many capped cells/pupae as eggs.

Queens

When examining a colony for queen issues, look for queen cells and other queen-related conditions. If the queen cells are toward the frame bottoms and numerous (greater than five or six), you probably have swarm cells. If the queen cells are toward the frame center and top and are less numerous (two or three), you probably have supercedure cells. If the queen cell is drawn from a worker cell and elongated, you probably have an emergency queen cell. Look to see if the bottom of the queen cell has been chewed open (raggedy edges). If so, a queen has emerged from the cell, and the workers have not yet torn the cell down.

Figure 1. Broad

Development Times

Figure 2 Swarm Cells/cups on the Frame Bottom with Two

Emergency Cells Midway up the Frame (Kathy Carpineto) Note the pollen between the Queen Cells and the Honey in the Upper left of the Frame.

Figure 4.

Healthy brood.

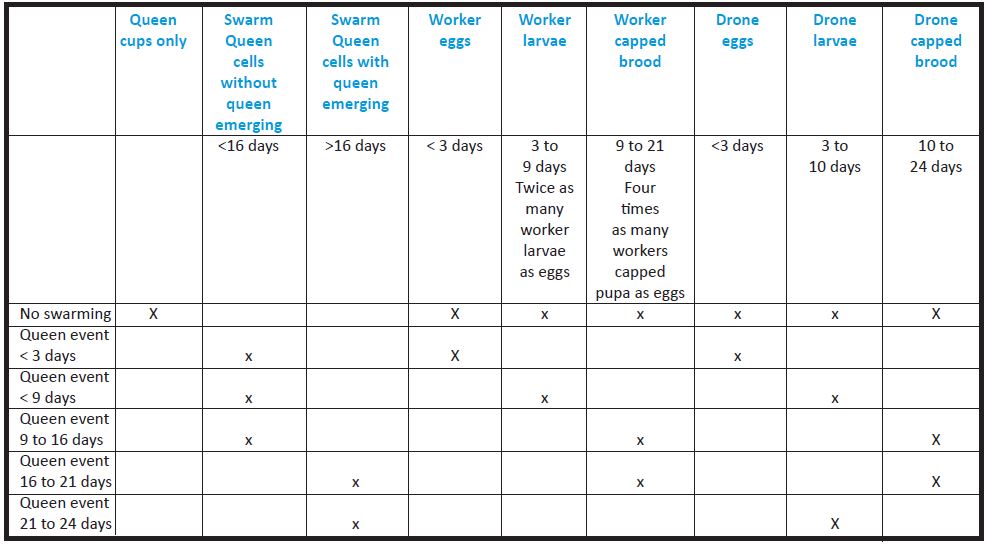

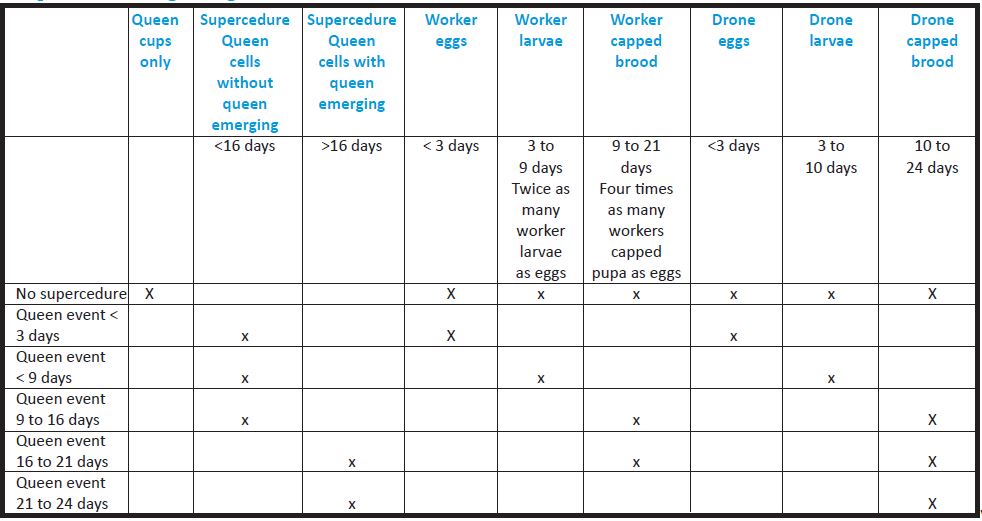

Other queen-related conditions also should be assessed. Look for worker brood (eggs, larvae, or capped) in the frames. If you have eggs or larvae, and the queen has not emerged from the queen cell, you know the colony recently swarmed, probably less than 16 days ago. If there are only capped worker brood, which is capped after approximately nine days, you know the colony probably swarmed nine to 21 days ago. If you have a queen cell from which the queen has emerged, together with capped worker and drone brood, you know the colony probably swarmed 16 to 21 days ago. If you have an empty queen cell, and have no capped worker brood but do have capped drone brood perhaps with some drones emerging, you know the colony probably swarmed 21 to 24 days ago, and you probably have a new queen that is getting ready to lay. After emerging, a new queen typically takes seven to 10 days to mate and start laying. Often, after swarming has occurred, the colony will backfill the brood nest with nectar/honey until the newly mated queen begins to lay.

Swarming: Diagnosing Queen Issues

Figure 5. Swarming: Diagnosing Queen Issues David MacFawn

Figure 6. Supercedure: Diagnosing Queen Issues David MacFawn

Laying workers

A laying-worker bee develops when the colony’s queen dies for some reason, and the colony is not successful in replacing her. This failure to replace the queen may be due to the colony having only larvae that are more than three days old when the queen dies, or the queen not returning from her mating flight. Sometimes a worker will start to lay, but her eggs are not fertilized. These eggs are known as drone eggs. The eggs are infertile since the worker has not mated with a drone and has no semen. This is the last effort for the colony to propagate the species. As brood pheromones that suppress workers from laying eggs diminish, a worker may start to lay. Laying workers usually take several weeks to develop after loss of a queen.

All workers are females with ovaries and the other egg-laying organs, but these organs are undeveloped due to suppression by the queen’s pheromones. When the queen disappears and is not replaced, her pheromones also disappear and with them, suppression of the worker’s ovary and egg development. As a result, a laying worker is created. The colony is still trying to pass on its genetics, but it can only do so if the laying workers produces drones that mate with a virgin queen from another colony in the Drone Congregation Area (DCA).

Figure 7 A frame of laying worker drone cells. (Photo courtesy:

Mark Sweatman)

Figure 8 Close-up of laying worker drone cells. (Photo courtesy:

Mark Sweatman)

The laying worker’s abdomen is typically not long enough to reach the cell’s bottom, so the eggs are laid on the cell sides , Multiple eggs are laid on each side of the cells. The bees enlarge the cells from worker cells to drone-size cells. Usually, worker drones are smaller than queen-laid drones. Laying workers lay more drones than a queen does, and the drones result in multiple combs/frames becoming all drone cells, effectively ruining the combs/frames for later use in producing worker bees.

Brood Nest

The pollen and honey define the brood nest boundaries, thereby defining the colony size. As a beekeeper, you should assess the brood nest by asking the following questions: Where are the outer frames of pollen and honey located in the brood nest? Where is the band of pollen above the brood nest? Where is the honey above the pollen band? Is this band of pollen in the bottom brood chamber or the super above? Is there a lack of pollen and honey in the frames? If there is a lack of pollen and honey, you may need to feed the colony.

Upon examination of the worker brood, larvae should be floating in food. If not, the colony has a nutrition issue. There is not enough honey and pollen for the nurse bees to produce the larvae food. The colony probably needs feeding.

Signs of wax moths and small hive beetles

Is there debris on the bottom boards of a hive? Are there other signs of wax moths or of small hive beetles (SHB) inside the hive? How much damage already exists from wax moths or SHB? Such conditions may suggest a hive in trouble. If you see wax moths and cocoons when removing the hive cover(s), look further down into the equipment stack to determine if you have a weak hive. Wax moths and wax moth cocoons are usually a sign that the colony is weak. The colony is not strong enough to manage the amount of space in the hive. If you have a weak colony, you need to determine if you should re-queen the colony, combine the colony with a stronger colony, or dispose of the colony. The extent of wax moth damage to the combs will assist you in making this decision.

Figure 9 Super with Advanced Wax Moths: Woodford, South

Carolina. David MacFawn

Figure 10 Frame with Advanced Wax Moth Damage. Woodford,

South Carolina. Taken by David MacFawn

Wax moths are attracted to the dark comb where brood has been raised. Hence, the challenge is to maintain your honey supers on the hive such that the queen does not lay brood in them. Wax moth eggs will not hatch at 64°F and are completely dormant below 41°F. This temperature sensitivity means that you should not have an issue with wax moths when outside temperatures fall below 64°F. You will have issues with SHB if you feed pollen patties in large quantities early. I found it best to control SHB by placing the patty directly above the brood nest in small quantities and feeding patties more often. Also, keeping the colonies in direct sunlight helps. SHB are usually not a large issue in January/February. You can use non-scented “Swiffer” pads to help control SHB during warm months. Very few honey bees get stuck in the pad.

Figure 11. SHB damaging comb. (Photo courtesy

Steve Seigler.)

Signs of American or European Foulbrood

A healthy bee has plenty of hair or/setae all over its body. Healthy brood looks “normal,” without sunken or perforated caps (American Foulbrood) or dark-colored larvae before capping (European Foulbrood). Healthy brood is not hardened like chalk (Chalk Brood). There should be no signs of exterior Varroa mites, and no deformed or distended wings (Varroa or viruses). If there are many dead bees (greater than 100) in front of the colony, and they look “greasy,” it may be due to pesticide poisoning. American Foulbrood (AFB) is caused by a spore-forming bacterium that will persist for decades. The infected worker pupa has sunken and perforated caps. When a small twig is inserted into the diseased cell, the infected pupa will “rope out” two to three inches. European Foulbrood (EFB) usually occurs in the larvae stage. EFB is considered a stress disease that is caused by a non-spore-forming bacterium and usually clears up with a nectar flow. Adding a frame of nurse bees will often clean up EFB.

Figure 12 SHB in advanced stage “sliming” comb.

(Photo courtesy Steve Seigler.)

Assessing Signs of Varroa Mites

Are there signs of varroa mites such as “snott” brood, varroa visible on drone brood, or deformed wings? “Snott” brood is present when many larvae brood are white and flowing in the cell bottoms. Often in Varroa loaded colonies, you can see varroa mites on a drone pupa when it is removed. Bees with deformed wings are also a sign of heavy Varroa mite loads that have resulted in Deformed Wing Virus (DWV).

An alcohol wash or some other method of determining the colony’s mite load should be done to determine your colony status. I refer you to Randy Oliver’s https://scientificbeekeeping.com/ website for further information on determining your colony’s Varroa mite status.

Summary

Observation of what is going on in a colony is key to determining the colony’s status. If and when the colony swarmed or superseded the queen, if the colony has wax moths or small hive beetles, if you have a laying worker situation, and if you have Varroa mites are all important in assessing the colony’s health, and this assessment will assist you in your treatment and remedy efforts for the colony.

This year the entire West and Northern Midwest is experiencing drought, leaving some growers with barely enough water to keep their crops healthy. Beekeepers are also struggling in places like North Dakota, where honey bees are preparing for almond pollination in February and some beekeepers are reporting record low honey crops. When nectar dries up, bees struggle to produce the honey they need to survive Winter.

Blooming cover crops benefit both beekeepers and growers by providing better nutrition for bees, increasing the soil’s water-holding capacity by adding organic matter, increasing water infiltration, reducing erosion, and providing natural weed control. Having forage available when bees arrive for pollination can help colonies build up strength after a tough year and ensure good pollination. On an exceptionally dry year, some cover crop plantings may not flourish as well as a year that sees average or above average rainfall. Even if your cover crops are not as robust as you might like them to be this year, the benefits are still valuable and are worth the effort.

What To Expect

Water is precious and promoting cover crops raises some important questions about water use. Seed blends intended to be planted in California’s Central Valley should contain species that have low moisture requirements. Sowing seeds in the fall is a great way to take advantage of fall and early Winter rains. If planted early to utilize the seasonal rains, robust, well-growing cover crop stands are possible without the use of irrigation. Early planting also encourages an early bloom which provides nutrition for honey bee colonies pollinating almonds. Planting September 10 through November 10, while soil is still warm (above 55⁰F) is an appropriate time to plant any cover crop in California. However, to ensure species like canola, mustard, and radish will bloom before almonds it must be sown and germinated before November 1. While not necessary for an adequate stand, irrigation can be used to ensure a more robust cover crop for some mixes.

Enrollees of Project Apis m’s (PAm) Seeds for Bees® program receive seed mixes designed to be successful in harsh conditions like the non-irrigated middles of orchards. If water availability is a concern, select seed mixes that are the most efficient at growing successfully in droughts. The PAm Clover Mix, for example, requires more moisture than the PAm Brassica Mix which can perform well with average seasonal rain, no irrigation needed.

Recent trials conducted by University of California Cooperative Extension researchers Shulamit Shroder and Jessie Kanter give some insight as to what growers can expect from a cover crop that is grown in drought conditions. During the 2020/2021 season, a variety of cover crop mixes were evaluated at the Shafter (Kern County) research station. Most of the irrigated seed mixes were more successful than the non-irrigated ones by providing about twice as much biomass, with the brassica mix being the exception as seen in Table 1 (Shroder, Shulamit and Kanter, Jessie 2021). However, they conclude “all of the non-irrigated plots contributed some amount of biomass. This means that even if you cannot irrigate your cover crops, you can still reap some soil health benefits.”

How Cover Crops Can Increase Water Use Efficiency

Growers who participate in Seeds for Bees receive technical advice specific to them, and our team will help you determine what mixes are most appropriate for your operation and water use goals. There is evidence to suggest that planting cover crops increases water use efficiency and water availability. Cover crops add organic matter to the soil. Organic matter is excellent at holding water; it works like a sponge that traps and retains water.

• Organic matter holds 18-20 times its weight in water (USDA NRCS 2013). One can expect the PAm Seed Mixes to provide about 3.5 tons of organic matter per acre.

• There are 1,000,000 tons of soil in six-inch deep acre plot, so growing a cover crop to about waist high will provide 0.03%-0.05% of organic matter every year. Just 1% organic matter in the top six inches holds up to 27,000 gallons of water! (USDA NRCS 2013).

Organic matter helps water stay where it’s needed most, around the root systems of crops. But cover crops also use water, so let’s take a closer look at how much water cover crops use in an orchard system.

How Much Water Do Cover Crops Use?

Cover crops grown in the fall and Winter months will need less water due to shorter days and cooler temperatures. More research needs to be done to determine how much water cover crops use from October to March. Typically, this is the time of the year when Seeds for Bees cover crops are growing. However, there is still something to be learned from a 1989 cover crop study that took place in an almond orchard from April to August. The results were published in California Agriculture in an article titled, “Orchard water use and soil characteristics,” by Prichard, et al. The results are shown in Table 2 (below). Resident vegetation (weeds), clover, bromegrass, and herbicide (bare ground) were the four treatments that were compared in two orchards: a newly planted one (Orchard A) and a mature one with 70% soil shading (Orchard B). The herbicide (bare ground) treatment used the least amount of water. Bromegrass used from 4% less to 18% more water than bare ground. Clover used more than bromegrass, 14% to 29% more than bare ground, and the most water was used by weedy resident vegetation, from 17% to 36% more than bare ground. A clover cover crop used less water than resident weeds! If something is growing on the orchard floor, it might as well be a cover crop. It will use less water than the weeds while increasing the soil’s water-holding capacity.

The 2021-2022 Seeds for Bees open enrollment period is happening now. Interested growers are encouraged to apply at ProjectApism.org/Seeds-For-Bees. We are currently accepting applications through November 15th, or until we run out of seed. California growers of all types can apply and first year applicants are awarded up to $2,000 of free seed. Don’t forget – early planting is key to getting the most benefit as possible from your cover crop stand. Sign up today!

Feel free to contact me, Billy Synk, at [email protected] for any questions regarding the Seeds for Bees program, cover crops, habitat, or bees/pollination

]]>