By: Shana Archibald

Ingredients

□ 1 cup honey

□ 4 cups all-purpose flour

□ 2 tablespoons baking powder

□ 1 teaspoon salt

□ 1 tablespoon cinnamon

□ 2 eggs

□ 2 cups milk

□ ⅔ cup vegetable oil

□ 1 large apple peeled and diced

Directions

Step 1

Preheat oven to 350°F.

Step 2

Combine flour, baking powder and salt. Set aside.

Step 3

Beat honey, eggs, milk and oil until combined.

Step 4

Gradually add dry mixture to wet until moist.

Step 5

Add apple and cinnamon.

Step 6

Grease baking dishes and pour mixture an inch below the top to compensate for rise.

Step 7

Combine cinnamon and sugar.

Step 8

Sprinkle a mixture of cinnamon and sugar onto each loaf and swirl in with a knife.

Step 9

Bake 40-50 minutes or until a toothpick comes out clean.

If you have read some of my articles, you know that my postcard collection influences some of my articles and this is no different.

Threshing Bee

A long time ago, wheat was loaded on to a wagon and hauled to an area where neighbors would get together and harvest it. The event was called a Threshing Bee and would be somewhat like a free carnival. Men would do the work with the wheat, women would help with the food for those working and children would help with the horses and carry items like food and water. The machine used was called a threshing machine and was usually powered by a steam engine. The threshing machine would separate the stalk and stems from the wheat. The event usually took a full day and then it might be held again at a neighbor’s place.

Where I grew up, people called it a thrashing bee. I never paid it any difference, but when my uncle got a combine, he let me ride in the grain hopper when the wheat or oats were harvested. Parts of mice and snakes would be dumped into the hopper along with the grain. It was truly a thrashing machine.

However, the event was still called a threshing bee, as it was a social event of neighbor helping neighbor.

In different parts of the world this help or fund raising activity is called:

Africa

East Africa – Harambee

Rwanda – Umuganda

Sudan – Naffir

Liberia – Kuu

Asia

Indonesia – Gotong-royong

Philippines – Bayanihan

Iran – Basij

Turkey – Imece

Europe

Finland and the Baltics – Talkoot

Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Poland – Toloka

Hungary – Kaláha

Ireland – Meitheal

Asturias – Andecha

Norway – Dugnad

Serbia – Moba

North America

Cherokee – Gadugi

Latin America

Mexico – Tequio

Zapoteca Quechua (including Peru, Ecuador, and Bolivia) – Mink’a

Brazil – Mutirão

Chile – Mingas

Panama – ‘Junta’ party

The earliest use of the word “bee” in colonial North America was found in the Boston Gazette in October 16, 1769, where 20 ladies held a Spinning Match or what is called a Spinning Bee. In Australia the term used is a “working bee.”

A Spinning Bee was originally a way to produce homespun cloth to reduce dependence on British goods and a way to protest British policies and taxation. Spinning bees not only were the spinning of yarn but also weaving it into cloth. The participants of the early spinning bees were usually young, unmarried women because they had the spare time for such work. Eventually it became a social event and women of many ages became involved.

There are all kinds of bees, such as: an Apple Bee, a Drinking Bee, a Husking Bee, a Logging Bee, a Quilting Bee, a Roofing Bee, a Sewing Bee, a Spelling Bee and others. Don’t forget the barn raisings or as they call it in the United Kingdom, a barn rearing. The “barn raising” could include churches.

Apple Bee – was a social event where the farmers helped gather the apples and prepare or process the fruit for drying.

Drinking Bee

Drinking Bee – has been replaced somewhat by binge drinking. Get the cheapest beer, the best beer funnel, a four-in-one beer opener and try to remember where the party is. However some may get in trouble by getting underage guests, so observe the laws. Now not everyone can afford to go to Germany or France where the drinking age for beer, wine and wine-like beverages starts at 16. However, there are ten countries where there is no stated minimum age. But when you find these countries, there are other restrictions, such as the drinking must be in private.

Husking Bee – is an older practice of cutting, shocking and husking corn. It would take a farmer several weeks to harvest his crop alone so he would ask the neighbors for help. He might not own all the equipment. Besides doing the crop, there were contests, such as who could husk a basket of corn first, and what young man could find a red ear of corn and kiss a girl before dinner? Today the farmers have machinery to do the picking, husking, shelling and drying. So I guess there are no girls to be kissed.

Logging Bee – one definition of a logging bee is another name for log rolling, but the original logging bees were the favorite way to clear space in the forests for the planting of crops. It was a social event and might take several days at each location. Again, we have bull dozers that replace axes, shovels and teams of horses or mules.

Quilting Bee – was a social gathering to make quilts or to hold competitions. The quilting bee was usually held in a large room where two quilting frames could be assembled and the women could finish several quilts in one day. Upon the ending of the session, a supper of roast chicken or turkey was prepared and the men would arrive for the feast, singing and dancing.

Roofing Bee – was an event where friends would come to your place and build, replace or repair your roof. Today it seems that this activity doesn’t exist. People are in the business to fix your roof for a fee, but will give you a choice in which color you would like and what type of material to use.

Sewing Bee

Sewing Bee – a social occasion where people get together to make or mend clothes and other things with a needle and thread while engaging in conversation. Today there is a television show, “The Great British Sewing Bee,” which is an elimination of a contestant each week. There are stores by the name Sewing Bee, that sell sewing supplies.

Spelling Bee – The earliest spelling bee dates back to 1825 however it had names like: Trials in Spelling, Spelling School, Spelling Match, Spelling-Fight, Spelling Combat and Spelldown. It was different from the other bees as it was an entertainment event. I also figure that the winner was the person that got the easiest word to spell. So it was the luck of the draw.

References:

Barn raising – Wikipedia.pdf

Communal work – Wikipedia.pdf

Why is it called a ‘Spelling Bee’ Merriam Webster.pdf

In this article we present a case study regarding an Apis mellifera honey bee colony with a heavy Varroa destructor mite infestation. When separated from the honey bees, these mites were examined using the integrated viral detection system (IVDS)1,2 and found to be actively infected by an unidentified virus. Interestingly, this virus was not found at all in the honey bees that were heavily infested with the mites. This raises the intriguing possibility that the honey bees may have acquired natural immunity to this particular virus while the mites remained susceptible. Such a virus may hold promise for the treatment of mite-infested bee colonies if it were shown to impact mites significantly without harming the bees. If so, this could represent a strategic avenue for treating mite infestations that merits further study.

The Varroa destructor mite is considered by many beekeepers to be the most problematic honey bee pest ever encountered3. These parasitic mites spend their entire life cycle with honey bee hosts. Female adult Varroa mites feed off of the fat of mature honey bees, causing stress, tissue damage and susceptibility to pathogens4. They reproduce on the honey bee brood and explode in population under suitable conditions. Female mites are highly mobile, crawling around the honey bee combs and in between adult bees (Figure 1). This mobility optimizes the mite’s capacity to act as a reservoir for any viruses that may be present. In many cases, the viruses can be dangerous pathogens. Deformed wing virus for example, prevents bees from flying properly. Not all viruses carried by the mites are equally as damaging to a bee colony. An additional possibility exists that there is a certain subset of viruses that are harmless to the honey bees but highly specific mite pathogens. Here we describe a case study in which we evaluate this possibility.

Figure 1. Apis mellifera honey bee with Varroa destructor mite infestation.

https://i.cbc.ca/1.3175886.1438368148!/fileImage/httpImage/image.jpg_gen/derivatives/16x9_1180/varroa-mite.jpg

The mite-infested bees described in this report came from the midwestern United States. The colony was in route to almond pollination in California and were having trouble making the six to eight frame grade. The problem was getting progressively worse. The beekeeper requested help from BVS, Inc. with additional investigation regarding this colony. Upon conducting our standard bee examination, the nosema fungal spore count was found to be negative and the average weight measurement was in the normal range of 0.12 grams per bee. Analysis for the presence of Varroa destructor mites revealed an infestation of 25 mites per 100 bees.

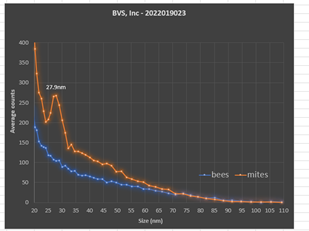

The first goal was to detect any viruses carried by either the honey bees or the mites. Frozen bees infested with mites were physically separated from one another and manually counted. The integrated viral detection system (IVDS) was used to examine each sample separately. The IVDS method1,2 involves enriching and concentrating viruses from biological samples according to their unique physical properties and then detecting those viral particles using an electrospray ionization-differential mobility analysis (ESI-DMA) approach. The IVDS strategy was developed and patented1 by the United States Army in order to detect and quantify all types of viruses and virus-like particles2. The goal was to isolate virus particles based upon their physical properties rather than rely upon chemical reactions. This strategy has proven to be effective over many years and is becoming even more practical in the current environment of supply chain disruptions and price inflation. Once virus particles are detected based upon their movement through an air flow and isolated according to their unique sizes, they are then quantified with a condensation particle counter. Our analysis revealed no significant presence of viral or viral-like particles in this colony of honey bees (Figure 2).

Figure 2. IVDS peak detection of unknown virus in mite samples.

We then analyzed 10 mites that were separated from the bees and prepared them for analysis in the same way as the bee samples were prepared. Analysis of the mites was done immediately after physically separating them from the bees. The mite tissue was processed using much lower quantities relative to the honey bee’s due to their lower biological mass. Therefore, we were concerned about difficulties with limits of detection for comparison purposes in the mites. However, we found the opposite. A very large peak detection was observed in the mite sample with no corresponding peak found in the bee tissue (Figure 2). Thus, it was likely that the difficulties suffered by this colony resulted primarily from the physical stress and tissue damage caused by the heavy mite infestation rather than from an active viral infection. Remaining mites associated with this colony are still available for study.

The implication of our observation is that an identified virus could conceivably be specific to the parasite and harmless to the host. Such a finding could point towards a treatment strategy for mitigating or even eliminating Varroa destructor infestations from Apis mellifera colonies. The idea of achieving biological pest control with pest-specific pathogens that are harmless to the surrounding environment is not a new idea5. Scientists at the Tamil Nadu Agricultural University in India have used the Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus (NPV) with some success to mitigate American bollworm, the tobacco cutworm and the red hairy caterpillar that attacks groundnut crops6. Likewise, NPV has been used to combat western tent caterpillars, African armyworms and invasive gypsy moths7. It has been proposed that the Southern pine bark beetle in Mississippi could be mitigated using a biological control method based upon naturally occurring viruses8. In the Czech Republic, the pine bark beetle Ips typographus was treated with the entomopox virus with some success9.

The aforementioned studies do not represent an exhaustive review of the field, yet it is clear that this approach has barely been explored. More research on this potential mitigation strategy is certainly warranted. Biological pests have natural enemies that are already part of the environment, and it may be possible to use them to our advantage. Such an approach could be part of an integrated pest management system and provide a complimentary method to help eradicate mite infestations. Our goals are directed primarily towards the detection, identification and characterization of naturally occurring viruses. We do not propose to genetically engineer those viruses in any way, given the history of unintended consequences with this approach.

We have already taken a large step forward by detecting a naturally occurring virus that clearly infects the infamous Varroa mite at high concentrations, apparently without infecting the honey bee host. We highlight that the IVDS approach is a valuable part of the toolkit for the discovery process. It requires measurement of an actual viral particle rather than detection of genetic sequence that may or may not represent an active infection. Importantly, a viral detection can be made without having to know the identity of the virus prior to looking for it.

Further steps would be to isolate the virus so that it could be sequenced. After that, the development of a mass spectrometry and PCR detection method specific to this virus could be developed. More studies are also needed to evaluate host specificity and any symptomology associated with viral infection.

REFERENCES

US Patent 8309029B1S8309029B1

Wick, CH, Integrated Virus Detection, Boca Raton, Fl. CRC Press (2015).

Rosenkranz P et al., Biology and control of Varroa destructor, Journal of Invertebrate Pathology (2009).

Ramsey, SD. et. al., Varroa destructor feeds primarily on honey bee fat body tissue and not hemolymph. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. (2019).

Metcalf CL et al. Destructive and Useful Insects, Their Habitats, and Control. New Delhi: Tata McGraw–Hill Publishing Company (1973).

https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/using-viruses-for-biological-pest-control-30309

Myers JH, et. al., Ecology and evolution of pathogens in natural populations of Lepidoptera. Evolutionary Applications (2015).

Sikorowski PP, et. al. Virus and Virus-Like Particles Found in Southern Pine Beetle Adults in Mississippi and Georgia https://www.mafes.msstate.edu/publications/technical-bulletins/tb212.pdf

Weiser J, et. al. Biological protection of forest against bark beetle outbreaks with poxvirus and other pathogens. IUAPPA, Section B (2000).

By: Becky Masterman and Bridget Mendel

Somewhere in Minnesota, in the biggest shopping mall in America, there is a small shop called Worker B (www.worker-b.com). This independent shop sells hand-made hive-based skincare products and honeys of all colors, from pale white, to dense, crystalized brown, red-gold or amber, to almost black. These are honeys from all over the globe, sourced by store owner Michael Sedlacek via a constellation of beekeeper friends and acquaintances. Mall visitors stop by to taste or buy honey, some looking for exotic flavors, others, searching for the particular taste of home, the sense-memory of some local flowering tree, a season, as captured by honey bees.

“Elsewhere in the world, honey is kept in high esteem. It’s maybe the most valued food,” says Michael, gesturing to a tiny batch of honey only produced in Yemen which he says is sought-after by his Middle Eastern customers.

Not all Americans share this reverent attitude. Some are surprised to learn that his honeys aren’t artificially infused with flavors, and instead are distillations of particular landscapes. Many of his local midwestern customers are used to one, homogenized “plain-sweet, grocery store” honey flavor, and are shocked by honeys tasting of cotton candy, prunes, molasses, mint or bitterness.

A unique retail experience, Worker B is located in the Mall of America, the largest shopping mall in the United States. Photo Credit: Mitchell Brown

And Michael is constantly searching for new honeys to meet the taste of long-time customers, and surprise new ones.

“We sell honey from tiny producers, who send batches pulled from particular nectar flows or some unique weather situation. So, we run out of things… We have to teach people to adjust their expectations, especially folks who are used to one flavor, or one consistent product.”

Somewhat unexpectedly, Michael describes his soon to be 200 varieties of honey as “all the same.” By which he means that, after thousands of hours manning the honey counter at the shop, Michael believes it’s all about celebrating the uniqueness of a particular honey. “Even if you don’t like it, it doesn’t mean it isn’t good,” he says. Rather than having a favorite variety, Michaels pulls a jar of honey like a tarot card from a deck, looking for stories.

What kind of stories? Stories about seasons, flowers, growth, climate, natural disasters.

Michael also hears a lot of stories from customers, about their connection to bees or to beekeeping, a particular sting or honey they recall from childhood. Often, deals are made right in the shop: a beekeeper walks in and asks, Would you be interested in honey sourced from persimmon trees in Illinois? Absolutely! Would he sell a few cases of honey produced after wildfires in the western United States, when chokecherries were all that bloomed? For sure, send a three ounce sample. Would you buy two dozen 10oz jars of zinnia-field honey? Oh, yes.

How about some clover honey? Well, not so much… Michael rarely takes the stuff; it just doesn’t interest him.

“The best honey comes from the beekeepers that care the most. You can feel it if people care. The honey feels alive. I don’t know what it is…”

Worker B is a business sustained by a unique confluence of factors: place, personality, and passion. Michael is outgoing, gregarious, and patient. While he describes the honey counter as a “challenging place to be,” you wouldn’t know it by his demeanor. While casually answering bee questions – Why is honey so expensive!? (it’s hard work to produce!) Can I buy your most expensive honey? (Sidr from Yemen, Samar from UAE and Melipona bee sourced from the Yucatan) who stop by this retail landmark on their way to the Mayo Clinic or elsewhere. Michael says the shop wouldn’t thrive without that stream of international folks who love and seek out rare honeys. Though, Michael has reached a fair number of locals, who may have come in looking for clover, but end up starting their own collections of unique honeys.

According to Worker B owner Michael Sedlacek, their skincare line (shown here) and honey sales proved to be a winning sales formula for their retail and online stores. Both lines need each other. Photo credit: Mitchell Brown

Like many small businesses, Worker B, a 12 year old institution, was massively affected by the global pandemic: Supply chains were disrupted, so imports halted. The Mall went dark. A business model dependent on members of the public standing elbow-to-elbow at a counter in a mall, licking honey off sticks, became unthinkable.

Pre-pandemic, Worker B had been in a phase of expansion, opening a spa and another honey shop. Everything closed down very fast, and bills piled up. “We are just not the same business as we were pre-pandemic.”

But Michael and his small team (cut to four from 22 by the pandemic) were determined to keep going, and incredibly, they did. They shipped honey and skincare products to a loyal customer base, and bided their time until the world opened up again. After all, the buying, selling and gifting of honey is a tradition that has persisted through every human catastrophe in recorded history.

Note: The authors disclose that Worker B has been selling University of Minnesota Bee Squad honey for many years.

Acknowledgement The authors would like to thank Dr. Marla Spivak for helpful edits and suggestions.

Becky Masterman led the UMN Bee Squad from 2013-2019. Bridget Mendel joined the Bee Squad in 2013 and has led the program since 2020. Photos of Becky (left) and Bridget (right) looking for their respective hives. If you would like to contact the authors with honey selling success stories or other thoughts, please send an email to

[email protected]

For centuries, communities in the Peruvian Amazon foraged for the hives of Amazonian stingless bees, meliponines, and used their honey and pollen to treat an array of conditions––from bronchitis and flu, to fertility (1,2).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Iquitos, Peru became one of the hardest hit areas. Hospitals and cemeteries overfilled, and, by April 2020, mass grave sites were improvised to accommodate the dead. As cities became hotspots for disease and death, rural communities turned to traditional healing and knowledge to treat the sick, including using the unique honey of Amazon stingless bees.

Community San Francisco, Nauta, Iquitos, Peru, 2021/12/16 – Rosa Vásquez Espinoza, National Geographic Explorer, biochemist and molecular biologist, studies bee hives, with Biologist Cesar Delgado (wearing green shirt) and local farmer Heriberto Vela (wearing plaid shirt), in a remote Peruvian community of the Amazon Basin.

For many Amazonian families, such as those in the communities of San Francisco and Chingana, beekeeping brought on much needed economic relief during the lockdown. During the pandemic, the demand and price for honey grew, and families were able to generate additional income from their home (1).

With support from the National Geographic Society, in December 2021, we traveled to outer Iqitos to learn about these bees and the medicinal properties of their honey. César Delgado Vásquez, who has been working with rural beekeepers in the area studying the links between the Amazonian stingless bee and plant diversity and growth, introduced us to a family of local beekeepers and to the magnificent world of

Amazonian stingless bees.

As we made our way up the Marañon River toward the town of San Francisco aboard a small speedboat and away from Nauta, the expanse of the forest became more visible, and its size was breathtaking.

Local farmer Heriberto Vela, holding a beehive in a remote Peruvian community of the Amazon Basin.

In San Francisco, Heriberto Vela, his wife Roxana, and their numerous children welcomed us into their home and showed us their beehives. César has been working with Heriberto and other local families by helping them set up and care for Amazonian stingless beehives (3). Because the bees don’t sting, locals are able to have many hives set up behind their homes. Heriberto’s children played in the forest and watched curiously as we opened up one of the hives.

The smell was as intoxicating as the shapes, colors and structure. Dark-colored cells make up each layer of the five leveled hives, and each layer serves a specific function: honey storage, larvae growth, disposal of the dead, etc (3). César pointed out the hive entrance, pollen stores, and egg cells, and acquainted us with the way of life of the bees––all the while they flew around us with rapid wing beats, buzzing and harmlessly resting on our bodies.

A local farmer holding a bee hive in a remote Peruvian community of the Amazon Basin.

It has been hypothesized that the bees’ honey acquires its medicinal properties from the plants they feed on, so Heriberto’s children gathered some of the plants for us. We examined the resin from Sangre de Grado trees (also known as dragon’s blood or Croton lechleri) which is used by the bees to build their hives and by locals used to treat diarrhea, infections, diabetes and cancer. We also examined the bright red achiote plant (Bixa orellana), which the bees feed on and locals used as a natural dye, for cooking and to treat constipation.

The pandemic devastated the Amazon Rainforest and the communities that depend on it as government vigilance decreased and illegal logging, farming, mining and contamination increased (4,5). Fortunately, the increase in beekeeping also brought on a rise of hard-working pollinizers, much needed in times of environmental crisis.

Previous research has shown that native bees are more effective in pollination of local crops than Apis mellifera (6). A recent study led by Peruvian entomologist César Delgado Vásquez in the Institute of Investigation in the Peruvian Amazon (IIAP) discovered that pollination associated with Amazonian stingless bees is directly contributing to an increase in the medicinal plant camu camu (Myrciaria dubia), with an up to 44 percent increase in crop yield (7). This result highlights the need to implement and promote meliponiculture practices in the Amazon to facilitate successful reforestation and strengthen agriculture productivity.

A bee carries dead larvae to the hive cemetery, inside a beehive in a remote Peruvian community of the Amazon Basin.

With Heriberto, we looked at the camu camu plant––which contains 30 times more vitamin C than oranges (7). By keeping multiple hives, Heriberto was contributing to the availability of these much needed plants in his agricultural crops.

We asked ourselves: Could bees help bring life back to the Amazon? While an increase in bees cannot tackle the damage brought on by incessant deforestation and oil contamination, an increase in bee population is directly linked to an increase in production and maintenance of local plants.

Nowadays, multiple factors threaten traditional Amazonian beekeeping practices: gradual loss of traditional knowledge, deforestation, low production and cost of honey, and an increase in extreme events such as flooding and drought. But by promoting meliponiculture practices in communities, we move the needle in repairing and preserving fragile areas of the Amazon Rainforest that could be critical in combating climate change (1,6). Local beekeeping of native species also creates job opportunities for people who protect and take care of the land, securing economic growth for generations to come.

Close up on a bee hive entrance in a remote Peruvian community of the Amazon Basin.

Successful and long-lasting preservation of the Amazon Rainforest, its flora, fauna and microbial life, requires multidisciplinary and creative action. Supporting exploratory science endeavors that deepen our understanding of Amazonian stingless bees and their traditionally used medicinal honey, especially from chemical and genetic angles, is critical. Capturing and portraying this research with an artistic lens that advocates for a more profound appreciation of meliponiculture, and its positive impacts in the jungle and its people, is equally important. Let’s advocate for conservation to take place at the intersection of science and art. Supporting Amazonian meliponiculture is an exemplary case of a practical solution with multiple benefits to the local agriculture, reforestation, biodiversity enhancement, and economy. While bees can’t fight mass destruction or diseases, in the long term and as a hive, these tiny warriors really can bring life back to the Amazon.

This research was funded by the National Geographic Society, which is a global nonprofit using the power of science, exploration, education and storytelling to illuminate and protect the wonder of our world. Learn more at natgeo.org.

References:

(1) Delgado, C., Mejía, K. and Rasmussen, C., 2020. Management practices and honey characteristics of Melipona eburnea in the Peruvian Amazon. Ciência Rural, 50.

(2) Delgado, C., et. al. Traditional knowledge of stingless bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Meliponini) in the Peruvian Amazon. Accepted in Ethnobiology Letters (currently in final edits)

(3) Delgado, C., Mejia, K., Sahut, A., Amorin, J. 2019. Manual para criar abejas sin aguijón con énfasis en la “ronsapilla” Meliponea Eburnea. Instituto de Investigación de la Amazonía Peruana.

(4) Stewart, P., Garvey, B., Torres, M. and Borges de Farias, T., 2021. Amazonian destruction, Bolsonaro and COVID-19: Neoliberalism unchained. Capital & Class, 45(2), pp.173-181.

(5) Brown, K. 2020. The hidden toll of lockdown on rainforests. Future Planet BBC.

(6) Garibaldi, L.A., Steffan-Dewenter, I., Winfree, R., Aizen, M.A., Bommarco, R., Cunningham, S.A., Kremen, C., Carvalheiro, L.G., Harder, L.D., Afik, O. and Bartomeus, I., 2013. Wild pollinators enhance fruit set of crops regardless of honey bee abundance. Science, 339(6127), pp.1608-1611.

(7) Delgado, C., Rasmussen, C. and Mejía, K., 2020. Asociación entre abejas sin aguijón (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Meliponini) y camu camu (Myrciaria dubia: Myrtaceae) en la Amazonía peruana. Development, 32, p.8.

On May 9, 2022, the United States International Trade Commission (USITC) voted unanimously that U.S. beekeepers producing raw honey were being materially injured by dumped imports of raw honey from Argentina, Brazil, India and Vietnam. This was the last step necessary in the trade case that was filed in April 2021 by the American Honey Producers Association (AHPA) and the Sioux Honey Association (SHA) to have an antidumping duty order imposed. The USITC found that imports were significant and undercut domestic prices, leading to poor and declining financial performance of the domestic industry. The USITC also found that critical circumstances applied to dumped imports of raw honey from Vietnam, which will result in antidumping duties being applied retroactively to dumped imports of honey from Vietnam going back to August 25, 2021.

I would like to thank the team at Kelley Drye for their work in helping us get this big win. Besides myself, Matt Halbgewachs from Exec. Board of AHPA, Ron Spears AHPA/Sue member, Alex Blumenthal, CEO of Sue and Craig Rodenberg of Sue all took time off to prep and then testify in the hearing. All did a great job.

When this antidumping duty investigation was initiated, importers and packers claimed that the imports were not being dumped and that the domestic industry was not being injured. The U.S. Department of Commerce (DOC) found that every exporter of honey in the subject countries was dumping honey in the United States. The unanimous affirmative injury decision by the USITC indicates the overwhelming evidence that unfairly traded imports, and no other factors, caused injury to the domestic industry.

The antidumping duty orders cover approximately 82 percent of imports of raw honey in 2021. As a result of the successful trade case, the prices of imported honey have risen significantly over the last year, which has allowed domestic prices to rise over the last year as well, as demonstrated by published prices. For the last several years, domestic honey producers as a whole have been unable to turn a profit on their honey producing operations. The increase in prices that the case has achieved should allow the domestic industry to begin recovering. Importers and packers now know that we are watching imports and will act to protect our businesses and way of life.

Now that the industry has some protection from unfairly traded imports, we will have to be vigilant to protect and maximize that relief. Our trade attorneys tell us that the DOC made some significant errors in the dumping margin calculations for India and Vietnam and that they should be higher. They are recommending that we appeal those decisions to ensure that we get the maximum relief from the orders. It is unclear whether any of the foreign producers or importers will appeal the dumping margins calculated for them. They have several more weeks in which to file any such appeals. If those foreign producers and importers do file appeals, it will be important that we intervene and participate to protect our hard-won relief.

It is also possible that importers and foreign producers will challenge the affirmative injury determination, and more likely that importers will challenge the critical circumstances determination which is costing them many millions of dollars in additional antidumping duty deposits. Once the time for appeals has run, our attorneys will provide us with options for participation in the proceedings to protect our relief from unfair trade.

This all costs money. The appeals process can take up to a year and we need more money to pay for it. If you have not donated yet to AHPA to help pay for this Win, please do so.

This case has been an important victory for the domestic industry and should provide the basis for recovery, just as the first dumping suit vs. China in 2001 brought relief for the industry. There will still be work to do to ensure we get the most out of the orders. We can be proud of what we have already achieved, however, and we will keep the industry informed of any ongoing efforts.

]]>

As I’m sure many of you know, World Bee Day is May 20. To celebrate, the Bee Culture staff worked with our employee council to do something special for all of the A.I. Root company employees. This year, we made goodie bags with some honey candy and sticks, a bee keychain, some pollinator seeds and little cards introducing the Bee Culture staff since we are all relatively new and many do not know us. We also gave each employee a copy of our May issue. Along with the bags, we worked with a local ice cream shop and passed out Lavender Honey Ice Cream to everyone. Overall, it was a very exciting experience for the whole company!

While the council did a quick first pass with the ice cream (it was in the 80’s that day!), Jerry, Emma and Jen went around slower to pass out bags and magazines and answer all of the bee questions many people had.

Jerry wore part of his beekeeping outfit for World Bee Day. He wanted to show off just how messy it can get sometimes, so he didn’t wash it!

By: Ed Erwin

To appreciate the uniqueness of the female honey bee stinger, it’s important to understand how this complex and distinct appendage evolved. The first bee evolved from wasp-like ancestors who were predatory hunting insects which were abundant during the Jurassic Period, beginning approximately 201.3 million years ago to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 145 million years ago. The Cretaceous was a warming period of the earth with many changes in biological diversity including the first mammals and the first true flowering plants. During the Jurassic Period, most of the plants reproduced by transferring pollen through the effects of wind. Like most of the flowering plants of today, the flowering plants of the Cretaceous period needed help in transferring pollen. To take advantage of this protein source, the wasp began to evolve into a pollen-carrying bee.

As the earth warmed during the Cretaceous Period, and the warmer climate created flowering plants which needed to be pollinated, the bee was evolving to become the perfect pollinator. This early bee was different than the honey bee we know today, which evolved around 25 million years ago. The modern honey bee was one of the first bee species to live in a group and not in solitary isolation. Along with this unique adaptation came the evolution of the honey bee stinger, which is a unique feature, suggesting that this evolved once the honey bees became a distinct genus.

As the earth warmed during the Cretaceous Period, and the warmer climate created flowering plants which needed to be pollinated, the bee was evolving to become the perfect pollinator. This early bee was different than the honey bee we know today, which evolved around 25 million years ago. The modern honey bee was one of the first bee species to live in a group and not in solitary isolation. Along with this unique adaptation came the evolution of the honey bee stinger, which is a unique feature, suggesting that this evolved once the honey bees became a distinct genus.

The stinging apparatus of the honey bee is a modified ovipositor (egg laying tube) with associated venom glands that all bees have. In most insects, the ovipositor is used to lay eggs.

The ancient wasps, like the wasps of today, use their stingers as a weapon to paralyze or kill their victims. The honey bee stinger is a complex structure made of many parts and is used as a weapon to defend the hive or the bee itself.

Male bees, also known as drones, are larger and do not have stingers at all. The queen bee has a smooth stinger, which she can use as a weapon.

When a honey bee stings, it grips its prey with its legs and pushes backward, pointing the sting shaft at its victim. This action forces the rigid stinger to a vertical, downwards angle.

The female honey bee stinger is a complex structure. The honey bee stinger is composed of several distinct parts that work in unison. The stinger consists of three key parts: a sharp sting shaft, or stylus, with two paired, barbed lancets at regular intervals running backwards and forwards located along opposite sides of the stylus. The bee does not push the stinger in but it is drawn in by muscular articulation that controls the movement of the barbed slides. The lancets move alternately up and down the stylus. When the barb on one side engages and retracts so that the barb of one slide has caught and retracts, it pulls the stylus and the other barbed slide into the wound – effectively sawing into the flesh. As the other barb catches, it retracts up the stylus pulling the stinger further in. This movement is repeated until the stinger is fully engaged to its maximum depth. This process continues even if the stinger is detached from the abdomen.

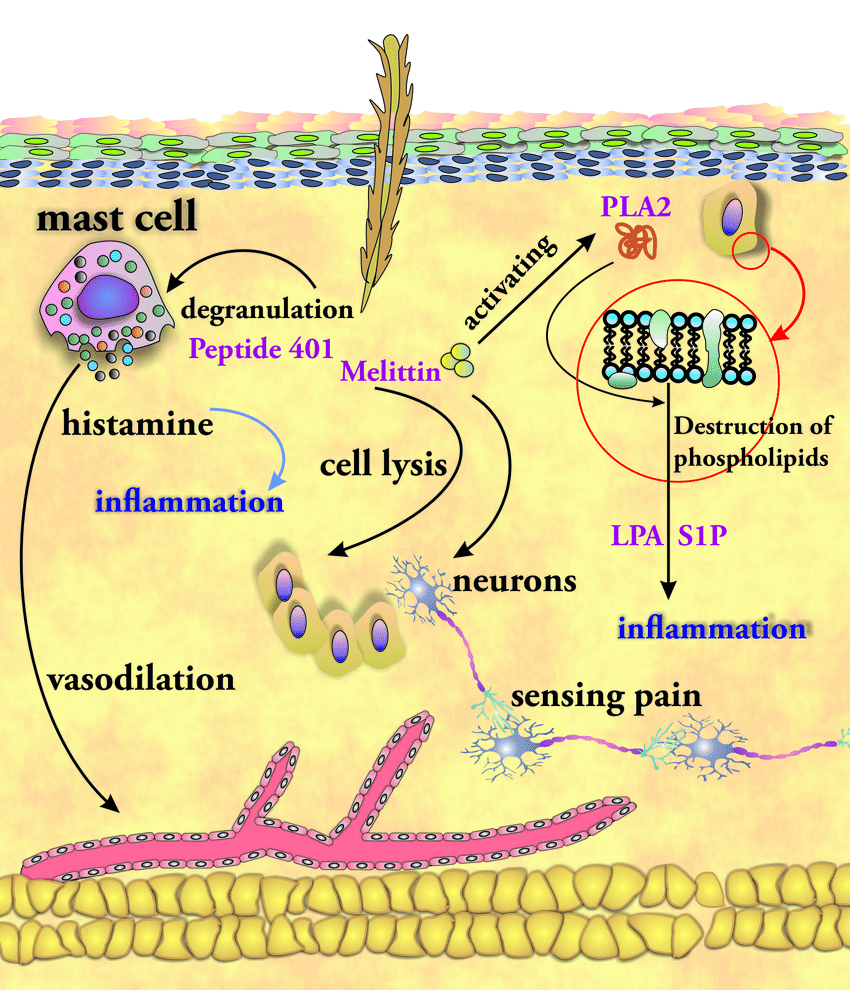

The stinger’s lethal venom, known as apitoxin, is a cytotoxic and hemotoxic bitter colorless liquid containing chemical compounds of proteins located in the venom gland, venom sack and bulb. Venom is 88 percent water, with fructose & glucose (sugars) and phospholipids (fat cells). The venom of the honey bee also contains histamine, mast cell degranulating peptide, melittin, phospholipase A2, hyaluronidase and acid phosphatase. The main component of bee venom responsible for pain and itching is the toxin melittin, a basic peptide consisting of 26 amino acids. These small protein molecules rupture red blood cells and bursts other cells in the blood vessels and skin. Although melittin is the main component and the major pain producing substance of honey bee venom, histamine is also released and causes inflammation by dilating blood vessels causing swelling and redness. An enzyme known as hyaluronidase is also released. It digests and breaks down the tissue in the flesh. This causes an increased rate at which the venom can diffuse. The three proteins in honey bee venom, which are important allergens, are phospholipase A2, hyaluronidase and acid phosphatase. When the bee injects the apitoxin into the victim, alarm pheromones are also released into the air alerting other bees to join in attacking the threat.

The stinger’s lethal venom, known as apitoxin, is a cytotoxic and hemotoxic bitter colorless liquid containing chemical compounds of proteins located in the venom gland, venom sack and bulb. Venom is 88 percent water, with fructose & glucose (sugars) and phospholipids (fat cells). The venom of the honey bee also contains histamine, mast cell degranulating peptide, melittin, phospholipase A2, hyaluronidase and acid phosphatase. The main component of bee venom responsible for pain and itching is the toxin melittin, a basic peptide consisting of 26 amino acids. These small protein molecules rupture red blood cells and bursts other cells in the blood vessels and skin. Although melittin is the main component and the major pain producing substance of honey bee venom, histamine is also released and causes inflammation by dilating blood vessels causing swelling and redness. An enzyme known as hyaluronidase is also released. It digests and breaks down the tissue in the flesh. This causes an increased rate at which the venom can diffuse. The three proteins in honey bee venom, which are important allergens, are phospholipase A2, hyaluronidase and acid phosphatase. When the bee injects the apitoxin into the victim, alarm pheromones are also released into the air alerting other bees to join in attacking the threat.

Bee venom is slightly acidic, and in most people causes only mild pain. However, more severe allergic reactions may occur in people with allergies to the venom components. Serious life-threatening anaphylactic reaction occurs in 0.8% of the population.

Several large muscles are used to facilitate the delivery of venom via the two pumps inside the venom gland. They, along with the venom storage sac, deliver the toxic venom to the stinger itself, which is only one or two millimeters in length. The sac contains about 1/50,000 oz of liquid venom. Depending on how long the stinger is allowed to pump venom, the amount injected is usually less than the 1/50,000 oz.

When the hive is attacked by other insects, bees can sting their foes multiple times, injecting venom and then removing the stinger safely after each stab. When a female honey bee stings a person, or an animal with flesh, it cannot pull the barbed stinger back out. As the honey bee flies away, the stinger tears off the body along with the venom sac, the muscular pumping mechanisms, parts of its abdomen, the digestive tract and nerves. The bee is disemboweled and massive abdominal rupture kills the honey bee. Although the bee is no longer connected, the stinger remains and continues to pump venom into the victim for 30 to 60 seconds.

Although there are thousands of species of bees, honey bees are the only bee species to possess barbed stingers and die after stinging.

Although there are thousands of species of bees, honey bees are the only bee species to possess barbed stingers and die after stinging.

Beekeepers know the main reasons bees become aggressive; include the need to protect their hive and honey, irritation of stormy weather and thunder, sensitivity to electromagnetic radiation, lack of nectar during the dearth, when a good honey flow stops abruptly and others, including Honey Bee Genetics. Beekeepers know that some hives are simply aggressive, which is usually the result of the genetics passed on by the queen to the entire colony of worker bees – a perfect example: Africanized Honey Bees. When bees become aggressive or need to defend their hive they use their stinger. Beekeepers know honey bees foraging for resources, such as nectar or pollen, rarely sting. The exception is if they are stepped on or feel threatened – so don’t swat foraging bees.

When people meet a beekeeper their first question is usually “have you been stung?” For most beekeepers the response is “Do you mean today?” For beekeepers, being stung on occasion is just part of the experience of beekeeping.

By: Alyssum Flowers

A garden should have a mixture of annuals, perennials and woody ornamentals to provide seasonal interest, height and structure. Adding a few bushes or even a small tree will enhance the garden’s dimension as well as create habitat and protection for small birds, or butterflies that need to escape a sudden downpour. One lovely addition could be a hydrangea! Two species that are especially attractive to pollinators are Hydrangea paniculata (panicle) and H. anomala (lace cap).

H. paniculata “Little Lime.”

https://www.monrovia.com/little-lime-174-hardy-hydrangea.html

Panicle or Peegee hydrangeas are a favorite in the landscape due to their dependable Winter hardiness, versatile multi-stem habit and graceful arching branches. Depending upon the variety, it can grow from three to eight feet tall and spread about the same. Plant it for privacy, as a hedge, or a focal point in the garden. From July through September, each branch ends in panicles of lacey white petals. As temperatures drop in the Fall, the petals fade to creamy yellow or pink while the leaves turn bronze-yellow.

Another reason that the panicle hydrangea is popular is that it is drought tolerant and can grow in a range of soil textures. It can be planted in Zones four to eight and grows well in the shade but can take partial sun as well. Prune this species in the zfall as the flower buds develop on Spring growth. Very few pests or diseases affect this plant, yet it fits into many landscape spaces.

The climbing or lace cap hydrangea is a strong climber that can be grown on gazebos, arbors, or even brick walls. In its native range of the Himalayas, China, this deciduous climber can reach 60 feet, but is usually maintained at six to 10 feet. Grown without a tall support, it will form mounds and spread laterally. It climbs with twining branches as well as aerial rootlets that are visually appealing. The bark is reddish and sheds strips of red colored bark (exfoliating) which is stunning in the Winter. Fragrant, creamy white flowers appear in early Summer and last for several weeks in shade or partial sun. In late Fall the glossy green leaves eventually turn yellow, adding to seasonal beauty.

H. paniculata “Quick Fire” https://www.monrovia.com/quick-fire-174-hardy-hydrangea.html

It is also Winter hardy to Zone four but although it will grow in clay soil, it prefers a loamy, well drained soil texture. Climbing hydrangea requires strong support to keep it upright. It is mostly pest and disease free but is harder to establish than other hydrangea species. Despite some drawbacks it is an outstanding addition to a landscape and will attract many pollinators.

References

https://plants.ces.ncsu.edu/plants/hydrangea-paniculata/

https://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/PlantFinder/PlantFinderDetails.aspx?taxonid=274441

https://landscapeplants.oregonstate.edu/plants/hydrangea-anomala-var-petiolaris

Hydrangea anomala https://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/PlantFinder/PlantFinderDetails.aspx?taxonid=286935&isprofile=0&