By: Fay Jarrett

Ingredients

□ 2 cups shredded zucchini

□ 1 pint fresh blueberries

□ 1 cup vegetable oil

□ 1 tablespoon vanilla extract

□ ½ cup & 2 tablespoons honey

□ 3 cups all-purpose flour

□ 1 cup powdered sugar

□ 1 tablespoon lemon juice

□ 1 tablespoon half & half cream

□ 3 eggs

□ 1 teaspoon salt

□ 1 teaspoon baking powder

□ ¼ teaspoon baking soda

Directions for Bread

Step 1

Preheat your oven to 350°F. Lightly grease either 2 large loaf pans or 4 mini loaf pans.

Step 2

In a large bowl, beat together eggs, oil, vanilla and honey. Fold in the zucchini. Beat in the flour, salt, baking powder and baking soda. Gently fold in blueberries. Pour into the prepared loaf pans.

Step 3

Bake for 50 minutes or until a toothpick comes out clean. Cool for 20 minutes and transfer to wire racks to cool completely.

Note: With honey, the bread will be a bit heavier and may take a little longer to bake.

Directions for Lemon Glaze

Step 1

Whisk together powdered sugar, lemon juice and cream.

Step 2

Drizzle on top of cooled bread.

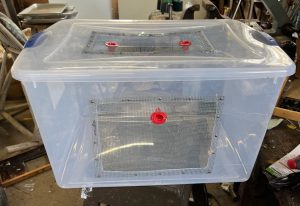

A large swarm shaken into the collection container with bees beginning to collect on the screen panels.

A decade or so ago I decided there had to be a better way to collect swarms than using an old cardboard box like I had done for many years. It seems that no matter how efficient I thought I was, I was never able to please the person who gave me a call about a swarm of bees collected from their property. I would return home thinking I had done a great job only to receive another call informing me that I left a million or so bees and I needed to come back and get them.

So, I started experimenting with different methods of shaking the swarms into various containers. Some were more efficient than others but none collected all the bees. Anyone

By late afternoon the bees have settled down and moved through the conical escapes into the container reforming the cluster with the queen.

who has collected a swarm knows that after the initial shaking of the bees that there are lots of confused bees flying around with many returning to the limb from whence they were originally located.

I eventually decided I needed some kind of one-way entrance on the collection box. Since I had used pollen traps to collect fresh pollen for my queen rearing cell starter/builders, I was familiar with the small red funnel shaped conical bee escapes that the traps used and decided to give them a try.

Most of my life I have not been lucky enough to come up with solutions on the first try but this was one of the very rare occasions where I did. I had been installing a #8 mesh screen panel or two on the storage tubs I used as collection boxes to help with ventilation when I

My favorite size and type of container, medium sized with latches for the lid.

transported the collected swarms to their new homes. My first inclination was to place one of the cones close to the screen which was moderately successful to enticing the flying bees inside, but some still hung out on the screen as I waited for the bees to settle down. I then moved the cones to the screen panels. This worked extremely well as I would shake the swarm in the container, replace the lid and sit the container on the ground in a shady spot as near the original spot where the swarm had collected as was possible. I would then leave the container in this spot until late afternoon or after sunset. By this time the swarm had settled down and around 99% or so of the bees had moved inside the box with the queen ready to be moved to their new home in one of my apiaries.

The key to success with these containers is to shake the bulk of the swarm, which includes the queen, into the container. To accomplish this, the swarm needs to be settled down in a tight cluster awaiting the scout bees to bring back info on a new home.

Cutouts finished ready to apply screen panels.

The cost of building this device is around $20, which in today’s world of beekeeping is a huge bargain. I use #8 mesh screen most of the time but have used aluminum window screen for the panels. There are many choices for containers and the one pictured in the construction photos is a 66-quart capacity which is a little larger than I normally use, but lately there has been a shortage of these storage tubs. I prefer the type that also use a latch type cover closure that keeps the lid secure during moving and transport.

Some of the tubs have holes hidden around and under the latches that bees can pass through, so be sure to check for these and plug them up.

Finished product with cones inserted/attached to screen panels.

The tubs have a shelf life with some lasting considerably longer than others, so I employ reusable fasteners when attaching the screen panels so I can reuse them. My preferred fasteners are #4 x ¼” SS sheet metal screws I buy from a marine hardware supplier for about $.03 each. I have used pop rivets, hot melt glue, wire stitching, staples and cap screws and nuts, but settled on the sheet metal screws being careful not to over torque them when screwing them into the plastic containers. The ¼” screws protrude out a little inside the container so I apply a dab of silicone caulk to them to cover the sharp edges and help hold them in place.

Mesh panels attached.

The screen panels are large enough to allow the bees to collect on them while providing ventilation but not so large that the cutout they cover jeopardizes the strength or integrity of the container. I fasten the cones to the screens with ⅜” staples from a manual stapler and bend the protruding ends over to secure the cones to the screens.

The photos of the construction are basically self-explanatory and I believe every beekeeper needs one or two of these devices. Once swarm season begins, I carry one or two of these collectors in my truck the entire season and have given away many. You can let the bees sit overnight in the container, but be advised that bees are persistant, and if you let them sit too long, they will figure out how to get back out through the escapes.

I use a template to mark the area I will cut out for the mesh panels. If you plan to pre-drill holes for fasteners, it’s advisable that you do so before cutting out the panels.

I believe it is very important for beekeepers to always answer swarm calls as it reinforces the public’s opinion that we truly care about honey bees and their welfare. This piece of equipment makes answering the call a little easier and more successful.

]]>By: Becky Masterman & Bridget Mendel

When Dr. John sings, “I been in the right place/But it must have been the wrong time,” he probably isn’t singing about beekeeping, but he sure sounds like a beekeeper griping about missing the nectar flow. We spent part of our Summer asking beekeepers to share their best advice on how to make a great honey crop. The first thing many beekeepers mention is being in the right place. Putting your bee near lots of good forage is key, but the right place won’t yield honey with the wrong timing. As Gary Reuter famously sang, “You can’t make honey if the supers are in the shed.”

Honey production is all about wedging your bees into the space/time continuum exactly right, and that takes practice, and practice takes years. We asked two, fourth generation beekeepers whose family businesses are now powered by the fifth generation what advice they would share with you. “Lessons of bee health and management timing are repeated until they are learned,” advised beekeeper and current president of the North Dakota Beekeepers Association, John Miller. Prior to retirement, John led Miller Honey Farms and their million-pounds-plus honey crop each year. His brother, Jay, Vice President of the American Beekeeping Federation and owner of 2J Honey Farms skipped to the punchline by quoting Carl Powers of Powers Apiaries, the biggest honey business around in 1960s, “Do what you should do when you should do it.”

Doing what you should do when you should do it takes practice. And part of the practice of beekeeping is being flexible and ready for strange seasons and disagreeable weather patterns. A late Spring, a wet Summer or a dry spell can affect the timing or abundance of nectars, our management choices and ultimately honey production. Though they chewed over weather plenty, none of the beekeepers we talked to had any good tips on negotiating with the weather gods.

Getting good honey also takes investing in the apiary and the surrounding landscape. Dr John sang, “I took the right road/But I must have took a wrong turn.” We took this lyric to refer to Dr. John’s fantasy of working with a commercial beekeeper. Locating beekeepers’ well-hidden apiaries is not a problem for the team of multi-talented Bee Informed Partnership (BIP) technicians. The BIP program, in whom many commercial beekeepers invest in to track mites and diseases in their operations, supports honey production by catching health problems while they can still be solved. You can get your supers out of the shed early and onto colonies, but if your bees are dying of mites and viruses they won’t fill up.

Supers “not making honey” while in the shed.

Photo Credit: Bridget Mendel

Beekeepers of all operation sizes emphasized the importance of keeping bees healthy, including monitoring and managing mites for productive bees. Some brought up the importance of new queens. Requeening in Spring is a practice that guarantees “fresh” queens: young, well-mated queens tend to be pretty productive, and more brood production means—you guessed it—a big population just in time for the basswood flow.

When asked to share honey production tips with Bee Culture readers, the beekeepers’ generous nature and willingness to help each other was evident. We hope you enjoy the following beebliography of honey production wisdom.

Meghan Milbrath, Assistant Professor in Michigan State’s Department of Entomology and owner of Sand Hill Bees: Put on supers early and often.

James Hillemeyer, owner of L. B. Werks, a honey and pollination business: Bring your (queen) operation in house. You get bigger honey crops with fresher queens. Time your population increase with the nectar flow.

Doug Ruby, owner of Ruby’s Apiaries, Inc. and commercial beekeeper in Minnesota and Texas: You need strong bees, good sub soil moisture and temperatures and a little luck.

Dan Whitney, owner of Whitney Lone Star Queen Co. and Dan’s Honey Co., beekeeper in Minnesota and Texas: You need a strong back, healthy bees and weather a little on the dry side.

A honey super being filled with fresh nectar, bees working on capping it.

Photo Credit: Rebecca Masterman

Dave Hackenberg, founder of Hackenberg Apiaries: You need the right kind of weather and to be on time.

Gary Honl, former owner of Honl’s Bees in Minnesota and Texas: You need the right location and habitat.

Dave Schroeder, Past President of the Minnesota Honey Producers Association and beekeeper in Minnesota and Wisconsin: Make sure there is good bee forage. Don’t be afraid to invest with the landowner.

Bob Sears, beekeeper in Missouri, national bee health advocate: Requeen every year with good queens, treat for mites, and super early.

Ryan Lamb, co-owner Lamb’s Honey Farm, commercial beekeeper in Texas and North Dakota: Add an extra pollen patty in the Spring.

Mark Sundberg, current president of the Minnesota Honey Producers Association, beekeeper in Minnesota and Mississippi, and owner of Sundberg Apiaries, Inc.: Be in the right place. Location and weather are important. You need good, strong, well fed and healthy hives.

Ang Roell, founder of They Keep Bees in Massachusetts: In our operation we let hives grow up on early flows then initiate a walk-away split. This gives them an extended brood break and they yield a nice honey crop while they’re making their new queen. It keeps our apiary genetics diverse and allows us to integrate both IPM & honey production in our queen breeding operation.

Becky Masterman led the UMN Bee Squad from

2013-2019. Bridget Mendel joined the Bee Squad in 2013 and has led the program since 2020. Photos of Becky (left) and Bridget (right) looking for their respective hives. If you would like to contact the authors with your own honey production tips or other thoughts, please send an email to

[email protected]

Stay tuned for Part 2 next month where we dive into some of the science behind a good honey crop and tell you why beekeepers are some of the best botanists around.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Marla Spivak for helpful edits and suggestions and John Miller for his history lesson on Powers Apiaries.

By: James E. Tew

“Hey, just combine them”

Combining colonies is a common procedure. As beekeepers, we do it all the time. Yes, we do it and we freely tell other beekeepers to do it. “Hey, just combine them.” Recently, in another piece I was writing, I made the following comment, “Any colonies that don’t take the new queens (or are weak) should probably be combined with another colony.” I was writing this statement in support of Fall Management protocols. As is so often the case, I made no recommendations as to how small the sickly “combinee” should be, nor did I make any reference to the population size and condition of the larger colony, the “combiner.” This fluidity is what I am exploring in this rambling article. Combining colonies is a very relaxed management recommendation.

Figure 1. The upper, weaker colony will be combined with the lower, stronger colony.

Not a natural procedure

Wild colonies die all the time. (At this point, I tried to find a generalized citation for just how often wild nests die. One was not readily available. Imidacloprids, water availability, and varroa predation were some of the reasons that feral colonies died. So, I will just leave it at, “Wild colonies die all the time.”) Colonies do not combine in nature; the weak colonies just die – or at least languish until they do die. (If this were a live presentation, I would expect a competent questioner to ask, “Do bees from dying colonies ever drift to more populous colonies?” That would be a good question, and I would not have a ready answer. I would most likely respond, “Probably, but I don’t know for sure.”) Robbing from more populous colonies is normally the coup de grâce for undersized colonies.

In beekeeping manipulations, we do these oddities all the time. Beekeepers collectively call these manipulations “colony management.” A wild colony does not go searching for a new queen outside its own colony. They always grow their own from their own brood.

In our human world, beekeepers show up in the bee yard with a caged queen – that has never been part of the colony to which she is about to be “introduced.” We then try to coerce the colony to accept this interloper. Or could I say be that the foreign queen is to be “combined” with the queenless colony? After the required introduction time, the queen is amalgamated (or combined) with the colony. The acceptance of a foreign queen is as unnatural as two feral, weakened colonies deciding to combine their meager resources, and become one. That’s not going to happen. They are both going to die before Winter’s end.

Beekeepers, when I think about it, bee management, in general, is just a long list of “oddities” that we do for (or to) our bees that they would never do for (or to) themselves. For example, wild colonies do not live in apiaries (groups), they don’t swap or share brood, they don’t add more space when their cavity is filled (supering) and they are not crazy about straight, standardized combs. So, no – combining colonies is not something that happens in nature, but it is something that happens in bee management – and it’s an old, useful procedure.

“Hey, just combine them” – again

Think about it. What are we actually accomplishing when we combine a weak colony with a stronger colony? Bottom line – we are giving the stronger colony the problem that we probably caused in the first place.

When considering laying workers, let’s look at this situation from the perspective of the stronger colony. Out of the clear, blue sky, in ways that would never happen in nature, a functional and staid colony suddenly has ten frames added to it – with some of the frames containing laying worker brood, and supported by a cadre of old, physically depleted workers. Within the hive, I have no idea how the bees sort this mess out, but I do have some guesses.

Figure 2. A newspaper sheet used to combine two colonies.

A series of assumptions

In ways unknown to me, I assume that healthy worker bees, from the receiving colony, perceive the laying worker eggs and brood and either eat or otherwise remove the haploid brood from the combined colony nest. I also assume that the adult laying workers most likely die of old age or from internal colony abuse. Until their death, any eggs that they may have continued to lay, will be – once again – destroyed by healthy worker bees. The undersized drones really have very little hope of any kind of success (I assume). In general, the undersized drones are just going to die. (In past articles in which I discussed laying

workers, I postulated that these puny drones were the last effort of the laying worker colony

to dispense its genetic strain into the greater gene pool. Regardless, these undersized drones – last effort or not – do not stand much of a chance for success.)

So yes, as bee colony managers, we all know that a “suitably strong” combiner colony can contain and clean up the failed situation. But… was the receiver colony improved or advanced by having to spend its time and energy getting this situation under control? I think not.

I speculate that two or three things happened in this laying worker scenario: (1) We beekeepers did not have to watch the bees from the smaller colony die, (2) we got our deep hive body back with ten frames all nicely cleared out and ready for reuse, and (3) the stronger colony protected the laying worker combs from wax moths. I speculate that rarely is the stronger colony made even stronger by the addition of a laying worker colony or any weakened colony for that matter.

Figure 3. Newsprint being removed 24 hours later.

What caused the weakness?

It is important to the beekeeper manager that they know the reason for the smaller colony weakness. For instance, during this past Spring season, I had a beautiful colony that seemingly would not stop swarming. While I got two swarms from that colony, I don’t know how many others got away. But by the time the swarming impulse waned, the once-beautiful colony was only a weakened shadow of its former self. Presently, I have no plans for combining this colony with another, but I know why this unit is now a smaller colony.

Queens age and their output declines. The season passes and worker population declines some. There are many reasons why a colony will be less than what it was just a few months ago. Don’t feel pressure to combine just because the colony’s population fluctuates some.

Please consider this – Important

Do not combine colonies that are diseased. Be able to recognize American foulbrood (AFB). Isn’t it ironic that beekeeper transmission is the main way AFB spreads? Thankfully, AFB is reasonably rare, but stunningly persistent. Make a major effort not to spread this disease – or any other – within your bee yard. If you are uncertain about any disease or another in-hive pest, gather more information or get the opinion of others.

Though off the subject, a comment on making splits is pertinent at this point. Do not make splits or take bees for colony increase from colonies that are diseased. Both combining colonies and splitting colonies are two common times that beekeepers can spread diseases in their apiary.

The timing

If you are combining colonies, the chances are excellent that a major nectar (or pollen flow) is not ongoing. Before a flow begins and during a flow, beekeepers would be in the “give the weak colony a chance” mode. As the food-gathering time passes and it becomes clearer that the colony is not going to thrive, then the concept of combining them with another colony becomes the standard option. So, what else is timely at this point? Robbing behavior.

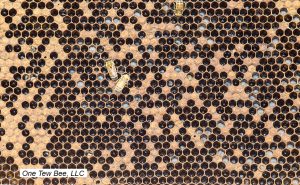

Figure 4. A colony with a brood pattern like this should be destroyed – not combined. This frame has American foulbrood.

In previous articles, I have seemingly had robbing behavior epiphanies, and I waxed long and then even longer in some of my earlier articles3. But based on my thoughts on robbing, if there is no flow ongoing, I can assure you that foragers from large colonies are not just sitting in the hive awaiting the day when once again flowers abound. Nope – they will be nosing around neighboring colonies checking their defenses.

At this point, let’s say that you begin the combining process. No flow is occurring, and you are opening two colonies – one very weak – and causing defensive confusion in both colonies. This situation would entice robbers to check out the confusion at the combined colonies. In the bright light of harsh reality, many times we would not be heartbroken to have the smaller colony robbed and killed. Its fate was sealed anyway, but we most likely did not want the healthier of the pair to also be attacked. That’s the colony that deserves our worry.

What to do? In a perfect world, we would move the colonies to a different yard. Then there is the reality of moving two colonies at least three miles away and the related problems that are associated with moving colonies. That is a different article. All this effort – all of this typing – all of this thought – is for a small bee colony that is actually nearly dead already. It’s what we do. We’re bee keepers, not bee killers.

Colony combining techniques

Shake the bees out of the equipment

The combining technique typically varies with the population of remaining bees in the dying colony. If there are only a few – maybe 200 to 300 bees – many beekeepers just shake them out of the equipment near another colony. They may or may not find their way into the nearby colony. We knew that would happen when we used this technique.

Newsprint sheet barrier

If – for whatever reason – there are more bees – maybe a thousand or more – a simple sheet of newspaper atop the stronger colony of the two is enough of a confusion barrier to seemingly distract the bees as they remove it from the combined hives. A few slits or a few punched holes through the newsprint is supposed to inspire the bees to remove it more quickly. The weaker colony is put on top of the lower, stronger colony. As per the title of this article, this is not a precise procedure.

A puzzlement… I wonder what happens between two opposing bees as they penetrate the newspaper and greet one another for the first time. Do they both smell and taste like newsprint? Do some newly introduced bees actually confront each other in an aggressive manner and beekeepers just do not see it? Rather, are the bees being combined defeated and placid? It does appear, that as newspaper is removed, the bees begin to amicably coexist. It’s a puzzlement to me that a simple piece of paper is enough to alter fundamental innate bee behavior. However, it appears that it does.

Smoke

Use smoke on both colonies. After removing the queen, if she is still present, shake the bees from the weaker colony onto the open top bars of the larger colony. Use appropriate smoke the entire time. Close the colony and remove the now empty equipment from the area. Then, hope for the best.

Sugar syrup

Use thin scented sugar syrup in the same manner as smoke. Spritz both colonies. Remove the queen from the weaker colony and while spritzing the scene, shake the combined bees onto the top bars of the stronger colony. Then, maybe another spray or two and close the colony up. Again, it is important to remove the empty equipment from the area.

Confinement

Using a package bee funnel, shake equal quantities of bees from both colonies into a package cage. Feed the combined bees enough to keep them alive for a few hours. Shake the bees back onto the top bars of the stronger parent colony. What you were trying to accomplish with this procedure was to have the foreign bees have the odor of the colony with which they were being combined.

When releasing the bees, maybe use a bit of smoke or some sugar syrup, but this step is not required. Close them up, and again, hope for a bit of good luck. To me, this process seems like a lot of work, but the procedure is in your management tool box if the need arises.

Everything is a variable

When using this concept of uniting colonies, there are numerous variables. For instance, how many small colonies do you have to combine? Are they tiny colonies or do they have respectable populations? Maybe you raised some queens, and you now have depleted nucs that need to be emptied. Maybe you picked up small swarms that did not grow to a suitable size. I’m speculating. I really don’t know why you have these small colonies, but you do have them.

Experienced beekeepers have indicated that they like to leave their good colonies alone and only perform combining procedures using “average” colonies as the receiving colony. Possibly, the average colony is helped by the additional bees. The management point is – do not disrupt your best colonies with these combination procedures. Also important, do not take excessive amounts of brood from good colonies to subsize combined colonies. Always remember that you are essentially working with dying bees.

One quirk without a category in this article

There is a situation when bee colonies – in a way – do combine themselves. Many years ago, when the Africanized honey bees (AHB) invasion was a major beekeeping issue, scientists reported that small swarms – headed either by mated or unmated AHB queens – would alite on a bee hive and invade the European stock within the hive. The invading bees would usurp the colony’s European queen and take over the colony. Were these colonies combining or were the European colonies simply being invaded? I am not aware of any recent reports of this happening, but just so you know…

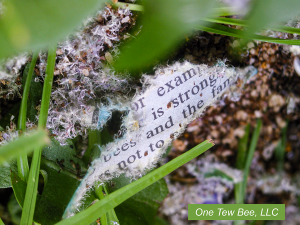

Figure 5. Frayed pieces of newspaper in front of colonies being combined.

In most instances

After thinking and writing on this subject, I sense that in most instances, when I have combined colonies, I was really just trying to get rid of the aged bees and get my empty equipment back. Additionally, I was trying to keep wax moths from overtaking the unprotected combs. I can’t think of a single instance when I ever combined a colony and then truly believed that I had a stronger colony because of the combination procedure.

This process seems to be a very useful way to eliminate bee colonies that simply did not make the grade. When keeping bees, you win some and you lose some. Combining bee colonies is simply a management tool. Use it when you need it. The bees will sort things out.

Dr. James E. Tew

Emeritus Faculty, Entomology

The Ohio State University

[email protected]

Co-Host, Honey Bee Obscura Podcast

Co-Host, Honey Bee Obscura Podcast

www.honeybeeobscura.com

]]>

By: Ross Conrad

This is the time of year when beekeepers throughout North America start preparing their colonies for Winter. Many beekeepers believe that bee hives should be insulated during Winter. The thinking is that the bees need help retaining heat inside the hive in order to survive the cold since wild bees that survive harsh Winters are often found in hollow trees with thick walls that provide more insulation than our typically thin-walled bee hives. This all sounds reasonable as long as you don’t consider the issue too closely. First, let’s take a look at how the bees prepare for Winter.

Unlike solitary native bees that hibernate, the Western or European honey bee (Apis mellifera) has evolved to be able to thermoregulate the hive interior in order to survive extreme cold weather. Research has demonstrated that a honey bee cluster must maintain a temperature within a range of about 90°F-97°F (32°C-36°C) to ensure brood survival (Heinrich 1981). Just like humans, during extreme cold temperatures honey bees rely on several heating strategies to thermoregulate their dwellings at the optimum temperature.

Efficiency first

Our heating bills can be greatly reduced with the well-placed application of caulk or weather stripping around windows, doors, plumbing pipes and other cracks in a building’s envelope where air leaks through. For larger gaps we often use spray foam insulation. Weatherizing a home for optimum efficiency provides the biggest bang for the buck when it comes to cold weather comfort. In a similar manner, bees will gather the resins from deciduous trees (e.g. cottonwood, poplar, birch and beech) and form it into propolis. The propolis is used it to plug up cracks and holes where air and light passes into and out of the nest cavity. This often includes adding propolis around the entrance to reduce the size of the opening to cut down on drafts and make it easier to defend.

Insulation on-demand

To most effectively conserve heat and maintain the brood nest temperature, bees will start to cluster around the brood area when the ambient temperature drops down to around 57°F (14°C). They position themselves in layers with the outside layer of bees oriented inward toward the middle of the cluster. This outer layer of bees will clump together tightly locking their legs forming a mantle-like shell surrounding the queen and the rest of the bees that are located in the interior of the cluster. Acting like the insulation layer of a building envelope, the mantle of bees retains the heat produced by the heater bees. In addition, the body hairs of the mantle bees interlock with their neighbors helping to trap the heat produced within the cluster enhancing the efficiency of the insulating effect.

Fueling heat generation

The center of the cluster is the warmest and safest area where the queen lays eggs and maintains the brood nest. Within and around the brood nest are heater bees. Just as we stack up our cordwood or have our fuel tank filled during the warm season so we can burn the fuel and produce heat in Winter, bees gather nectar during the Summer, store it as honey and burn these carbohydrate calories during Winter to help fuel heat generation. Heater bees generate body heat by flexing their thoracic flight muscles (endothermic heating) much like the human body will create heat by shivering. Along with heater bees there may be fanning bees that help to move the warm air around depending on the temperature and how tight the cluster is.

Ventilation and temperature control

The bees maintain porous air channels to help regulate the warmth, humidity and CO2 levels within the cluster. When temperatures drop further, the cluster will contract, becoming tighter and more compact. This action will close up unneeded porous ventilation channels.

A healthy colony that stays dry and has access to plenty of honey does not need a well insulated hive in order to thrive. Bees have been

insulating their Winter cluster long before beekeepers came along.

Thus, the honey bee provides an excellent example of what we all should do during Winter, get together with those closest to us and snuggle. They also are smart about how they heat their home by focusing the energy demands of heating only in the area they are occupying rather than trying and keep the entire interior of their hive cavity warm. This mimics how one might maintain comfortable temperatures in a home with a heating ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) system designed with zones that minimize heat in areas such as utility rooms and other places that have lower temperature requirements than the rest of the building.

The center of the Winter cluster serves as the central heating system for the colony. Worker bees take turns performing endothermic heating, fanning and serving as mantle bees rotating in and out of the various roles. Human beings utilize a centralized control system such as a thermostat that monitors the room temperature and turns on the heat when the temperature drops below a certain level. Unlike us humans that tend to rely on a centralized control-system, the bees employ a decentralized control system. This decentralized system relies on each honey bee’s individual assessment of what is needed (heating, fanning, shielding) based on the immediate local temperature and humidity. Unlike humans, bees do not rely on a single temperature point to respond, but utilize the experience of multiple and redundant individual bee’s which allows for rapid resolution of any disturbance or change to in-hive environmental conditions. This means that increased genetic diversity in a queen’s offspring through high levels of multiple mating creates more stable brood nest temperatures. Diverse colonies sired by numerous males increases the genetically determined diversity in worker bee’s temperature response thresholds. This modulates the hive-ventilating behavior of individual workers, helping to prevent extreme colony-level responses to temperature swings (Jones et. al. 2004).

Hive insulation

Now let’s get back to the question of how important beekeeper applied hive insulation really is.

While not easy to pin down precisely, it appears that softwoods such as pine have an insulation value of R-1.00 to 1.25 per inch (USDA 2007). While some equipment manufacturers make a big deal out of the extra insulating value of the thicker lumber they use to make their hive bodies, the thermal difference between a ¾-inch thick board used to manufacture most modern hives and thicker lumber is so minimal that insulation claims are more marketing hype than potential benefit to the bees. Other equipment manufacturers and suppliers provide equipment made from Styrofoam, or offer insulating blankets for wrapping hives in Winter. These products provide significant extra insulating value and can have a noticeable impact on the temperature of the hive’s interior. I won’t deny that under some unique circumstances such increased hive insulation may be beneficial, but the reality is that it is much more likely that beekeeper efforts to super insulate hives are more harmful than helpful.

Since there is always an entrance opening that allows cold air to enter the hive, the interior of a hive surrounding the cluster will eventually grow cold during long stretches of low temperature weather. However, as long as a colony is healthy with a large population of bees, stays dry and has access to fuel (honey), the bees are able to compensate for the cold by thermoregulating the interior of the cluster as described above. Hive insulation only acts to slow down how quickly the ambient interior temperature around the cluster of the hive will cool down.

Unfortunately this also works in reverse. When there is a Winter thaw and temperatures increase during the day, the temperature modulating effect of hive insulation slows down the speed with which the interior warms up allowing the bees to break their cluster and go on important cleansing flights. Unlike the decentralized insulation created by the mantle bees in the cluster, beekeeper applied insulation does not respond to rapid and dramatic temperature shifts and can be detrimental for overwintering bees. Heavily insulated hives can also delay a colonies population growth in Spring.

In warm climates where Winter temperatures are not so extreme and ambient temperatures surrounding the cluster inside the hive do not get excessively low, hive insulation may not create much of a problem, but then the insulation is also not really needed. Unfortunately, in northern climates where one would assume that increased hive insulation would be most beneficial and temperature extremes swing widely and sometimes rapidly, the delay in hive warming during a Winter thaw can prove devastating to a colony.

Hive insulation above the inner cover can help keep a colony from getting wet during a Winter thaw. Materials such as straw and burlap will absorb some of the moisture above the cluster, while rigid foam insulation simply prevents the water from freezing, allowing the moisture to be vented from the hive, provided there is adequate air flow.

So is insulation a necessary hive component for Winter? I would argue that except perhaps in some unique circumstances, the answer most of the time is no. Just make sure the three primary factors are met. 1) The bees are healthy with a large population. This means that mites are under control and disease issues are not a factor. 2) Colonies should be heavy with plenty of honey. There should not be a lot of unused empty space, undrawn foundation or empty combs in the hive and the honey stores should be concentrated primarily in an area of the hive that the bees will be able to access easily. 3) The bees are able to stay dry. Not only does this mean that the hive covers are secured so they will not accidentally come off, but condensation that naturally builds up in the hive will not freeze above the cluster only to drip down on the bees during a thaw. As I have outlined in the book Natural Beekeeping, pay attention to these three factors and the bees will be able to keep themselves warm and comfortable all Winter. After seeing thousands of colonies housed in standard Langstroth hives with no extra hive insulation successfully over-winter in Vermont, despite temperatures that can get down to 15°F to 20°F below zero (-26°C to -29°C) during Winter, it has convinced me that the effort spent super insulating hives is probably a waste of time, money and resources.

Ross Conrad is the author of Natural Beekeeping: Revised and Expanded 2nd Edition, and The Land of Milk and Honey: A history of beekeeping in Vermont.

References:

Heinrich, Bernd (1981) Insects thermoregulation, New York, Wiley

Jones, J.C., Myerscough, M.R., Graham, S., Oldroyd, B.P. (2004) Honey bee nest thermoregulation: Diversity Promotes Stability, Science, vol. 305, Issue 5682 pp. 402-404

U.S. Department of Agriculture (2007) Thermal conductivity of selected hardwoods and softwoods, The Encyclopedia of Wood, Skyhorse Publishing Inc. pg 3-20

Canadian Association of Professional Apiculturists Preliminary report on Honey Bee Wintering Losses in Canada (2022)

Canadian Association of Professional Apiculturists Preliminary report on Honey Bee Wintering Losses in Canada (2022)

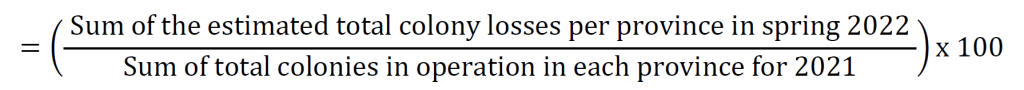

This report presents the preliminary data collected by the provinces of Canada regarding honey bee losses for the Winter of 2021-2022. The final data will be published in the annual Statement on honey bee wintering losses in Canada. There may be discrepancies between results in the preliminary and final reports.

Methodology

Beekeepers that owned and operated a specified minimum number of colonies (Table 1) were included in the survey. The survey reported data from full-sized producing honey bee colonies that were wintered in Canada, but not nucleus (partial) colonies. Thus, the information gathered provides a valid assessment of honey bee losses and commercial management practices.

Table 1. Survey Parameters and honey bee colony mortality (2021-2022) by province |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province | Total number of colonies operated in 2021 | Estimated number of colonies lost based on the estimated provincial Winter loss | Type of data collection | Number of beekeepers targeted by survey | Number of respondents (% of participation) | Size of beekeeping operations targeted by survey (# colonies) | Number of respondents’ colonies that were wintered in Fall 2021 | Number of respondents’ colonies that were alive and viable in Spring 2022 | Percentage of surveyed colonies as a proportion of the total number of colonies in the province | Provincial Winter Loss including Non-viable Colonies |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 700 | 153 | 12 | 11 (92%) | 20 | 596 | 466 | 85% | 21.8% | |

| Prince Edward Island | 6,800 | 3,527 | 50 | 20 (40%) | 1 | 5,294 | 2,548 | 78% | 51.9% | |

| Nova Scotia | 27,115 | 4,130 | 41 | 15 (37%) | 50 | 17,613 | 14,930 | 65% | 15.2% | |

| New Brunswick | 13,250 | 2,621 | Email, mail, telephone | 31 | 22 (71%) | 50 | 10,408 | 8,349 | 79% | 19.8% |

| Quebec | 55,974 | 27,504 | Online | 130 | 79 (61%) | 50 | 48,611 | 24,725 | 87% | 49.1% |

| Ontario | 102,328 | 48,374 | Online, telephone | 203 | 94 (46%) | 50 | 32,240 | 16,999 | 32% | 47.3% |

| Manitoba | 114,837 | 65,687 | Email, online | 178 | 65 (37%) | 50 | 71,492 | 30,614 | 62% | 57.2% |

| Saskatchewan | 115,000 | 39,724 | Online | 341 | 99 (29%) | 50 | 45,833 | 30,001 | 40% | 34.5% |

| Alberta | 319,922 | 161,511 | Online | 182 | 83 (46%) | 100 | 189,448 | 93,806 | 59% | 50.5% |

| British Columbia | 62,000 | 19,931 | Online | 262 | 106 (40%) | 25 | 24,024 | 16,301 | 39% | 32.1% |

| CANADA | 817,926 | 373,163 | 1,430 | 594 (42%) | 445,559 | 238,739 | 54% | 45.6% | ||

The common definitions of a honey bee colony and a commercially viable honey bee colony in Spring that were used in the survey were as the following:

Honey Bee Colony: A full-sized honey bee colony either in a single or double brood chamber, not including nucleus colonies (splits).

Viable Honey Bee Colony in Spring: A honey bee colony that survived winter, with a minimum of four frames with 75% of the comb area covered with bees on both sides on May 1st (British Columbia), May 15th (New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Prince-Edward-Island and Quebec) or May 21st (Alberta, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Newfoundland and Labrador).

The questionnaire of colony loss and management was provided to producers using various methods of delivery including mail, email, an online survey and a telephone survey; the method of delivery varied by jurisdiction (Table 1). In each province, data were collected and analyzed by the Provincial Apiarist. All reported provincial results were then analyzed and summarized at the national level. The national percent Winter loss was calculated as follows:

Percentage Winter Loss

Preliminary results

The survey delivery methods, size of beekeeping operations and response rate of beekeepers for each province are presented in Table 1. It is important to note that the total number of colonies operated in a province reported by this survey may vary slightly from Statistics Canada official numbers. In some provinces, the data collection periods for the provincial database and the Statistics Canada report are done at different times of year. This can result in minor discrepancies between the official Statistics Canada total number of colonies and this survey’s total reported colonies per province.