Click Here if you listened. We’re trying to gauge interest so only one question is required; however, there is a spot for feedback!

Read along below!

The Quiet Evolution of Apiary Mowing

The Quiet Evolution of Apiary Mowing

A Necessary Aspect of Apiary Management

By: James E. Tew

My First Real Job

When I was a young teenager, a friend and I would push our mowers around the community and offer to cut grass. We generally earned somewhere between $1.75-2.50 per yard total. We had to split the earnings. The mowers were not self-propelled. Consequently, as young entrepreneurs, we never had a body weight problem.

We developed a regular customer list and at our peak, we were cutting about twenty lawns per week. General expectations were that we cut in straight lines and tips were not offered. When we were thirsty, we drank water from faucets plumbed from the house. Dad provided the mower and the gas, but I was allowed to keep my earnings. Of course, he got his lawn cut for free.

To this day, I cut grass in bullet-straight lines, and I only mow when the lawn absolutely needs it. Now, throughout every Summer month, I marvel at the equipment that professional mowing services have and I compare all that modern equipment to the absolute minimal equipment that my friend and I used all those years ago. Times change, don’t they?

Before Gasoline Mowers

Before gasoline mowers became widely available, lawns were cut using various manual methods and tools. The common methods used for lawn maintenance before gasoline mowers were scythes, sickles, weed slings, grazing animals, manual push mowers and scissors. None of these options were feasible without manual labor. Even grazing animals required fence installation. The invention of gasoline-powered mowers modernized lawn care and made it much more efficient and accessible for homeowners, landscapers and even beekeepers.

Figure 1. A Kansas beeyard in 1920. Note beekeeper in the lower left of the photo who is wearing a vintage Alexander veil and gauntlet gloves.

What Did this Mean for Apiaries?

It means that our apiaries, decades ago were weedier, and more unkempt by today’s standards. I cannot find information indicating that grazing animals were common methods for foliage management in pre-mower days. No doubt, cows, horses and sheep would occasionally knock over hives or scratch against them.

In the past, all apiary grass and weeds were cut manually requiring hot labor commitments. I’m old enough to remember life before string trimmers and herbicides. Everything was weedier then.

Figure 2. In 1922, in this Iowa beeyard, all grass was cut using manual methods. Gasoline mowers, of the day, were heavy and uncommon.

To Add to the Laborious Task

In years past, just as the present, protective bee gear was commonly worn when cutting and pruning near bee hives. Wearing protective equipment was just as clumsy now as it was years ago. The requirement to wear protective clothing has always made apiary weed control a hot, tiring job. Thankfully, modern protective equipment is better ventilated and more comfortable, but it is still hot work.

No-Mow May

Due to my early years of incessantly cutting grass, as a senior citizen, I am now a reluctant lawn mower. To the chagrin of my neighbors whose lawns are always neatly manicured, I only mow when I must. In this way, I avoid needless mowing sessions and my bees have access to the clover and dandelions in my lawn.

When I first heard of the concept, I readily embraced the notion of a “No-Mow May” in which we just give our lawns a month off from trimming. I quickly found out that a mow-less May lead me directly into a hellish June, with tall grass that frequently required raking after cutting. I had to go back to the lawn maintenance drawing board.

String Trimmers in the Apiary

I don’t remember the first time I used a string trimmer. With my mowing history that I touted before, that memory void seems strange to me. But I do know that a string trimmer became a necessary component of the equipment that always went with me to an outyard. String trimmers are now a common, if unexciting, beeyard management tool. What’s their story?

A Short History of String Trimmers

The history of string trimmers, also known as weed whackers, weed eaters or line trimmers, dates to the early 1970s. The concept of using a rotating nylon string to trim grass and weeds emerged as an alternative to traditional lawn mowers and manual cutting tools.

The concept of a rotating nylon line for cutting vegetation was developed in the late 1960s by George Ballas, a Houston-based entrepreneur. He got the idea while watching the revolving brushes at a car wash (I find this interesting. The common safety razor was envisioned after a visionary watched a woodworker use a common hand plane. The flail honey comb uncapper was conceptualized as another visionary watched the conveyor belt perform at a grocery store checkout. Shouldn’t we all be more observant?). In 1971, he received a patent for his invention, which consisted of a fishing reel with fishing line attached to the spool. Ballas’ invention was the foundation for the modern string trimmer.

In 1972, George Ballas partnered with Jim Goad, an engineer, to refine the design and create the first commercial string trimmer. They established the Weed Eater company and introduced the first gas-powered, handheld string trimmer to the market. This model quickly gained popularity due to its effectiveness in trimming grass and weeds in hard-to-reach areas.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, electric string trimmers began to appear on the market. These models were lighter and quieter than their gas-powered counterparts, making them more appealing to homeowners with smaller yards.

Bees and Trimmers

No matter how useful power mowers and trimmers may be, on some mowing days, the bees seem to despise them. Most experienced beekeepers have seen this defensive behavior. In fact, common management recommendations warn the beekeeper to expect this attack. It is thought that the odors and vibrations from the mowers and trimmers agitate the bees.

In my own experience gained when trimming around hives, it seems that the bee response is greatest during Summer months when a nectar dearth has ended and the colonies are at full populations.

I have never used a battery-powered trimmer, but I am sure some of you have. I ask if you have noticed less of a response when using battery-powered mowers and trimmers? Does their quietness and lack of fumes have a more lenient effect on the colonies?

Beekeepers and Trimmers

At this moment, I have two, hand-held string trimmers. I have one modified with a cutting blade for heavy or tough growth. Brambles, such as multiflora rose, are a challenge for either type of cutting head.

Even though I frequently use them, I increasingly have issues with string trimmers. The evolving issue is that the older I become, my trimming sessions grow shorter and shorter. My shoulders ache. I get noise warnings from my Apple watch. I get hotter and hotter in the protective gear that I must wear. I simply can’t do the job the way I once could.

Figure 3. An apiary with uncontrolled grass growth.

Consequently, I have grown to dread the task more and more. All the while, the grass and weeds have continued to grow. Out of necessity, I developed a tolerant attitude of tall grasses and weeds in my apiary. I put my hives on firm hive stands that were twenty inches from the ground and I kept the entrance free of tall weeds. Even then, the grass and weeds in my beeyard continued to grow. My bees seemed unphased by the tall grass in the yards, but increasingly, it became apparent that this approach could not last. Why?

Two reasons that altered my laissez-faire system of yard maintenance evolved. The first reason was you, the reader of Bee Culture articles. Photos and videos that I captured in my apiary looked terrible. For instance, while I wanted to write about a new swarm that I just acquired, my photo of the new bee hive was marred by tall grass and the appearance of a generally unmanaged area. (If you have back issues of Bee Culture, you can readily see these photos.) I grew afraid that you, the reader, would not understand the bigger picture.

Figure 4. A manicured yard that uses herbicides, grazing animals and electric fencing to keeps foliage at bay. C. Parton Photo

Secondly, the tall weeds made it difficult for me walk while carrying a super of honey or other related bee equipment. Briars tugged at my suit. Tall grass made me stumble as I walked. Grass grew in and around my unused equipment. As with the No-Mow May scenario that I discussed earlier, I had to return to the drawing board. I was physically unable to trim my entire beeyard with a string trimmer and it was too much to ask of my 1972 Snapper push mower to systematically mow this tall grass.

A Heavy Duty, Walk-Behind Trimmer

I would occasionally see advertisements for various models of walk-behind trimmers. I asked around my circle of beekeeping friends, but no one had experience with these machines. I checked online. Yes, wheel kits were available for my string trimmers. In theory, I could modify my handheld trimmers to be mobile. Again, I asked around my circle of beekeeping friends, but no one had experience with these wheel kits either. All the while, the grass continued to grow. Would a trimmer on wheels allow me to work longer and more consistently?

Figure 5. A walk-behind Cord Trimmer.

In mid-July, with apiary grass higher than my knees, I broke. This situation in my apiary was unacceptable and was never going to get better. I went to an equipment dealer to buy a wheel kit. They did not have one, but they did have a single walk-behind trimmer on the showroom floor. It was $400. I bought it on the spot. It uses four .175” spiral cutting cords and cuts a twenty-two-inch swatch. It cuts at five heights – from 1.5” to 3.5”. I set it to the highest setting. The machine fairly easily chewed through the tall weeds leaving me with a somewhat rough-looking finished job, but the weeds were readily cut down.

The nose on the machine does a reasonably good job of getting beneath my hive stands – not perfect – but reasonably good. The cords are not cost free and they do wear out, but the machine aggressively took out tall weeds. It worked.

The major drawback is that I must still push the machine through tall grass. That requires old fashioned perspiration, but it’s still easier than using a handheld string unit. Please know that I am not selling these units. I’m only looking for a yard maintenance remedy.

For beekeepers younger than or more physically fit than I am, a typical string trimmer would get the job done. As I have written in previous articles, I’m at a stage of my beekeeping where I try to put wheels on everything. String trimmers were no exception. I should also say that while the bees didn’t go crazy, I still needed to wear light protective gear when using the machine.

Figure 6. Weed whacking beneath hives.

Hot and Clumsy

This past July 2023 was the hottest July every recorded. Yet the grass kept growing. To keep the grass under control, grass-cutting beekeepers are hot, and clumsy, and are surrounded by irate bees. Can it get any worse? Yes, it can, at the same time, we are also using power mowing equipment. Occasionally, accidents happen. This is a beekeeper’s recent story.

Figure 7. Accidents happen quickly. Attacking bees can be distracting. Many of us have a story.

I got home from work and my wife wanted to cut the grass but she’d never used that particular riding mower. I changed out of my work boots into my Crocs and pulled the mower out of the garage for her. I decided to make a couple passes by my bee hives so my wife wouldn’t get stung.

My bees have never bothered me before. On the first pass, I had hundreds of bees come after me. They were stinging me so much that I was fearful I might have an allergic reaction. I quickly decided to jump off the riding mower and make a run for the house. My foot got caught in the pulley and belt on the mower deck. My croc stayed lodged in the mower belt while I ran into the house. When I got inside and got all the bees off me, I realized how badly my foot was hurt.

I went to the Emergency Room where they said it had broken my toe and cut a tendon. It almost cut my toe off. I had 12 stitches and had to wear a Draco shoe that keeps the weight on my heel and off my toe until my broken toe can heal.

Mowing is Not Beekeeping

Every apiary mowing situation is different but presently, we have an abundance of diversified mowing devices. That selection of devices does not mean that mowing is not hot, demanding work. Don’t go crazy cutting grass and weeds, but when you do mow, I would suggest wearing heavy shoes and a ventilated bee suit with a veil that opens to allow for water sips. Have a lit smoker at the ready. Mowing is not beekeeping. Pace yourself.

Thank you.

I appreciate you reading and sending any comments that you may have. Your time is valuable. I know that.

Dr. James E. Tew

Dr. James E. Tew

Emeritus Faculty, Entomology

The Ohio State University

[email protected]

Co-Host, Honey Bee

Obscura Podcast

www.honeybeeobscura.com

Click Here if you listened. We’re trying to gauge interest so only one question is required; however, there is a spot for feedback!

Read along below!

Beekeeping

A Doorway to Nature

By: Ross Conrad

It has been suggested that a spiritual crisis is at the center of the long emergency we collectively face. This crisis manifests itself as a disconnect from the natural world and is considered by many to be one of the primary forces driving the growing degradation of environmental health. When we see ourselves as separate from the natural world, we view nature through the lens of how valuable it is to us personally, either economically or for its beauty. This is the typical Western approach to the notion of pristine wilderness. When we place such values on the natural world and its “resources” viewing it simply as a means to gain financial wealth or other material benefits, it can reinforce our separation from it.

Research indicates that people who have a strong emotional and spiritual connection to nature are more likely to behave positively towards the environment, wildlife and habitats. This suggests that nurturing a greater connection to the natural world among the general population may be critical in addressing our spiritual crisis and helping to reverse the current environmental emergency. There are many ways this nurturing of our connection can manifest including hiking and camping, fishing and hunting, farming and gardening, or bird watching.

For the readers of Bee Culture, beekeeping likely provides one of our primary windows into the natural world. Through beekeeping, we enter the fascinating world of the honey bee; from the waggle dance and the intricacies of swarm behavior, to honey bee biology and the production, use, and unique characteristics of the products of the hive. Our fascination with bees stems from our personal connection to them and our deep understanding of them and their ways. It has been claimed that the honey bee and beekeeping is the most studied and written about topic in the world, second only to us humans. The truth of course, is that all living creatures are absolutely fascinating: we just tend to be clueless to most of the wonder, beauty and amazing intricacies and relationships involved in the lives of the plants, animals and insects that surround us and that we may come into contact with. We simply don’t interact with them enough to understand them and their ways, as well as we do the honey bee, and this can result in their being under-appreciated.

The world of beekeeping acts as a doorway through which we are able to then connect with the wider natural world of all the pests, diseases, plants and weather patterns that impact our bees; for better or worse.

The truth is that we are not separate from nature and the earth. Our bodies are literally made of the same minerals of the earth; we live our lives on the earth surrounded by the natural world; and when we die our body goes back to the earth and eventually gets recycled by the natural world. What we do to the natural world, we do to ourselves. We may not die when a rare pollinator dies out and becomes extinct, but surely a small part of something within us dies, something sacred and precious.

A host of studies have pointed to the fact that the stronger our personal connection to the natural world, the greater our concern for the environment (Whitburn et al., 2019; Mackay and Smidtt, 2019). There is also strong evidence of a positive relationship between a person’s connection to the natural world and one’s personal health, wellbeing and happiness (Capaldi et al., 2014; Barragan-Jason et al., 2023). When individuals are exposed to natural environments, such as mountain tops, coastlines, meadows and forests, the exposure results in stress reduction and assists in mental recovery following intense cognitive activities. It has even been found that a hospital window view onto a garden-like scene can be influential in reducing patients’ postoperative recovery periods and analgesic requirements.

Beekeeping provides a doorway through which individuals can develop a strong spiritual connection to the natural world, especially those living in urban or suburban environments.

Embedded in diverse cultures around the world is the idea that people consciously and unconsciously seek connections with the natural world. The theory that this is a result of evolutionary history where humans have lived in intimate contact with nature was initially put forward by Harvard biologist and two-time Pulitzer prize-winner, E.O. Wilson, in the Biophilia hypothesis (Wilson, 1984). We humans appear to be innately attracted to other living organisms. Evidence suggests that this is particularly evident when life becomes difficult and stressful. How many of us can deny the relaxing effect of a quiet moment by a lake, the soothing effect of sitting by a river, the rejuvenation of a hike through a forest, a stress reducing stroll by the seaside, the calming effect of simply cuddling with a pet dog or cat, or spending time with the honey bee colonies in our apiaries. Simply put, we need contact with nature and the importance of our ability to connect with the natural world has only grown due to our increasingly urban, digital-screen and social media lifestyles that often serve to disconnect us from nature which in turn, may contribute to health and wellbeing problems.

One meta-analysis suggests positive short- and long-term health outcomes with improved self-esteem and mood with exposure to green environments. Proximity to water generated some of the greatest changes and the mentally ill experience the greatest self-esteem improvements (Barton and Pretty, 2010). Other researchers examining the link between finding meaning in life and our relationship to the natural world suggest numerous benefits that arise from a personal connection to the natural world. Not only does nature help us find meaning in life, it can enhance our appreciation for life, and how engaging in nature-based activities (such as beekeeping) “provides an avenue for many people to build meaningful lives” (Passmore and Krouse, 2023).

The idea that contact with nature benefits our mental and physical health appears to be strongly supported by the statistics. According to one researcher, “Animals have always played a prominent part in human life. Today, more people go to zoos each year than to all professional sporting events. A total of 56% of U.S. households own pets. Animals comprise more than 90% of the characters used in language acquisition and counting in children’s preschool books. Numerous studies establish that household animals are considered family members; we talk to them as if they were human, we carry their photographs, we share our bedrooms with them” (Frumkin, 2001).

Beekeepers have their own version of this in what is referred to as the “telling of the bees.” A tradition where it is believed that when the beekeeper dies, someone has to go tell the bees and perhaps hang a piece of black cloth on the hive to place it in mourning or else the colony would die out or abandon the hive. There appears to be many versions of this. Others tell the bees about important events in their lives particularly regarding a death in the family. Considering how easy it is for a beekeeper to put off caring for their bees with our busy lives, this tradition practically served as a way to keep the hives in the thoughts of those that survive a deceased beekeeper, so that they will hopefully prioritize finding a new custodian to take over responsibility for their care in a timely manner.

As a deep personal connection to the natural world, beekeeping has the potential to provide numerous benefits to its participants. Beekeeping encourages one to get exercise along with fresh air and sunshine, and there is significant evidence that suggests that even the occasional bee sting can help fortify the body’s immune system allowing it to more effectively deal with various ailments (provided of course that the person is not hyper allergic to honey bee venom). Beyond all this, we now know that beekeeping can also help establish a spiritual connection to the earth and all the life forms with which we share this planet; a connection that may be critical in our ability to effectively deal with our current reliance on damaging green-house gas emitting technologies that are slowly turning our lives and society upside down.

Many people are suggesting that the weather extremes we have been experiencing around the country and the world is the problem, when really the problem at its base level is the malevolent actions of individual people. Nurturing a greater connection to the natural world in greater numbers of people, such as through activities like beekeeping, might just hold part of the salvation for this world. Something to consider as you go about the business of caring for your bees this Autumn and are tucking your colonies in for the long Winter ahead.

Just the same as a month before,—

The house and the trees,

The barn’s brown gable, the vine by the door,—

Nothing changed but the hives of bees.

Before them, under the garden wall,

Forward and back,

Went drearily singing the chore-girl small,

Draping each hive with a shred of black.

Trembling, I listened: the Summer sun

Had the chill of snow;

For I knew she was telling the bees of one

Gone on the journey we all must go!

An excerpt from the poem Telling the Bees by John Greenleaf Whittier.

Read the full poem here: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45491/telling-the-bees

Ross Conrad is the author of Natural Beekeeping, Revised and Expanded 2nd Edition, and coauthor of The Land of Milk and Honey: A history of beekeeping in Vermont.

References:

Barragan-Jason, G., Loreau, M., de Mazancourt, C., Singer, M.C., Parmesan, C. (2023) Psychological and physical connections with nature improve both human well-being and nature conservation: A systematic review of meta-analyses, Biological Conservation, Volume 277:109842

Barton J, Pretty J. (2010) What is the best dose of nature and green exercise for improving mental health? A multi-study analysis. Environmental Science & Technology, 44(10):3947-55. doi: 10.1021/es903183r. PMID: 20337470.

Capaldi, C.A., Dopko, R.L., Zelenski, J.M. (2014) The relationship between nature connectedness and happiness: a meta-analysis, Frontiers in Psychology, Volume 5

Howard Frumkin, (2001) Beyond Toxicity: Human health and the natural environment, American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 20(3):234-240, ISSN 0749-3797, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00317-2

Mackay, C.M.L. and Schmitt, M.T. (2019) Do people who feel connected to nature do more to protect it? A meta-analysis, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 65:101323

Passmore, Holli-Anne and Krouse, Ashley, N. (2023) The Beyond-Human Natural World: Providing Meaning and Making Meaning, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(12):6170

Whitburn, J., Linklater, W., Abrahamse, W. (2019) Meta-Analysis of human connection to nature and proenvironmental behavior, Conservation Biology, https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13381

Wilson, E. O. (1984) Biophilia: the Human Bond with Other Species.: Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Click Here if you listened. We’re trying to gauge interest so only one question is required; however, there is a spot for feedback!

Read along below!

Found in Translation

Mite Drop!

By: Jay Evans, USDA Beltsville Bee Lab

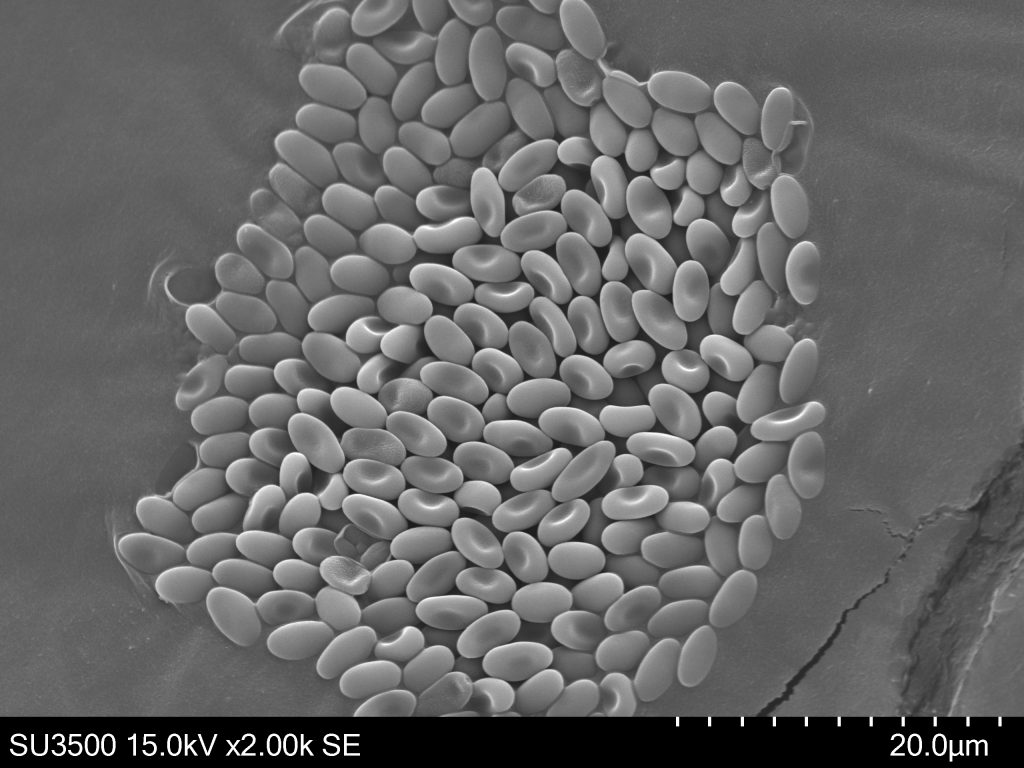

Varroa mites remain the primary source of honey bee colony losses for beekeepers managing from one to 10,000 colonies. Scientists like us and ardent beekeepers are always on the hunt for new ways to reduce varroa damage to bees and their colonies. One intriguing strategy is to make mites simply fall off their adult bee hosts. Short of changing the electric charge of host or parasite, this repellency can come from 1) making hosts less grippy, 2) somehow clogging the incredibly strong tarsi (feet with ‘toes’ and a spongy, oily, arolia) of mites or 3) affecting mite behavior by making them less likely to find safe spots and hang on to their bees for dear life. Dislodged mites are far more vulnerable to hygienic worker bees and might also simply keep falling down to a hostless, hungry and hopefully, short life. This is probably a central reason that female varroa mites spend very little time wandering the combs of beehives unless they are moments away from entering the brood cell of a developing bee. While on adult bees, mites have much incentive to stay right there, whatever their host is doing to drop them.

How do mites adhere to their bees so strongly? When mites are actively feeding on bees they are extremely hard to dislodge, since they are partly under the hardened plates of the bee itself and are gripping with a combination of ‘teeth’ and tarsi. Even while taking a break from feeding, mites know to find safe spots on the bee to attach, favoring locations on the abdomen or thorax that are both hairy and away from swinging legs and biting bee mandibles. How can one make them quit their bees given so many hiding places?

How do mites adhere to their bees so strongly? When mites are actively feeding on bees they are extremely hard to dislodge, since they are partly under the hardened plates of the bee itself and are gripping with a combination of ‘teeth’ and tarsi. Even while taking a break from feeding, mites know to find safe spots on the bee to attach, favoring locations on the abdomen or thorax that are both hairy and away from swinging legs and biting bee mandibles. How can one make them quit their bees given so many hiding places?

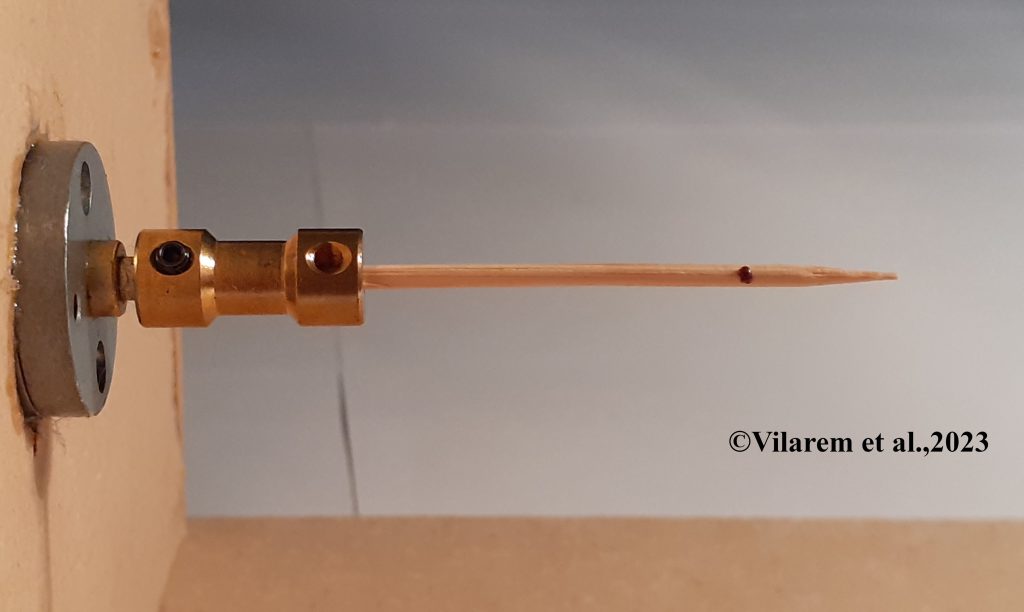

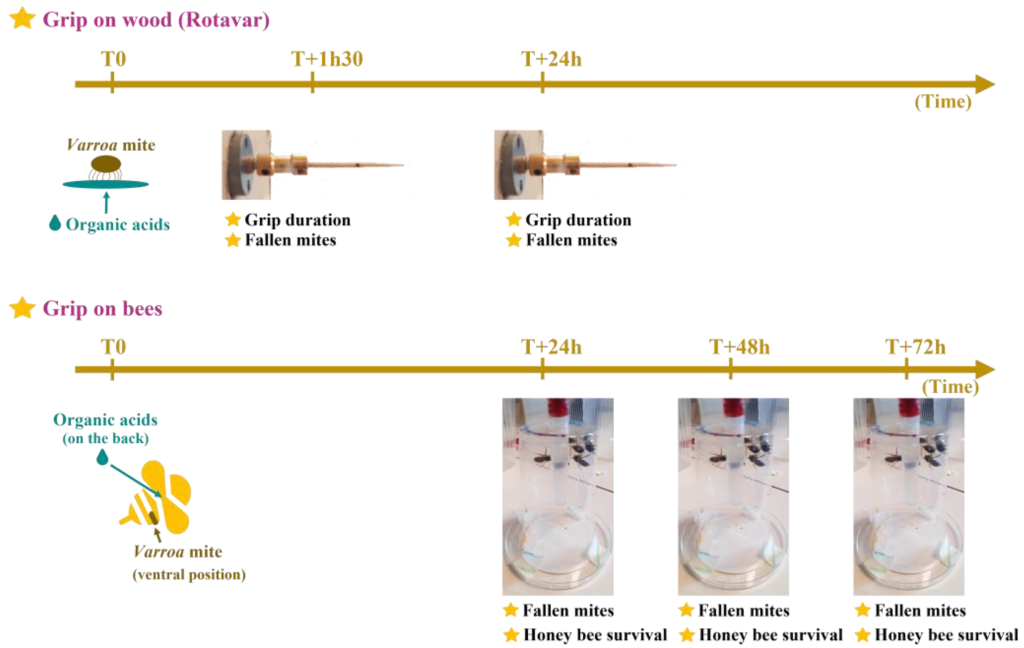

Caroline Vilarem and colleagues in France recently described an ambitious attempt to document the abilities of mites to hang onto surfaces when exposed to organic acids (Vilarem, C.; Piou, V.; Blanchard, S.; Vogelweith, F.; Vétillard, A. Lose Your Grip: Challenging Varroa destructor Host Attachment with Tartaric, Lactic, Formic, and Citric Acids, Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9085. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13169085). These scientists deployed one of the coolest low-tech tools to measure how well mites grip onto a surface. While their ‘Rotavar’ sounds both complex and expensive, it is actually a ‘motor-driven rotating toothpick’. Yes, you can do this at home, with a slow (three or so revolutions per minute) motor and a supply of toothpicks. The authors add to that an extremely careful experimental design and complex statistics to show the different abilities of mites to hang onto sticks and bees coated with acetic, citric, lactic, formic and tartaric acids. The results hint at new modes and new candidates for mite control, with the usual caveat that converting a controlled lab assay to field colonies will be challenging.

Schematic diagram of the experimental design and measured parameters. Grip on wood (Rotavar): This method relies on direct contact between Varroa’s arolia and the organic acids. The Rotavar set-up is a motor-driven rotating toothpick used to assess V. destructor’s grip. Grip on bees: the host attachment experiment applies acids to the backs of honey bees to remove mites. T0 represents the administration time for treatments; T + 1 h 30, 24 h, 48 h, or 72 h stand for the time post administration used to make measurements. Figure from https://doi.org/10.3390/app13169085

Some highlights: First, acidity itself does not seem to be the solution. Most notably, even high doses of acetic acid had little impact on the abilities of mites to grab toothpicks and this candidate was quickly discarded. So, what can we glean from the differences between the tested acids? Tartaric acid worked great at dislodging mites from spinning toothpicks but was surprisingly poor at dislodging mites from bees. Prior work suggests that the mode of action for tartaric acid is, at least in part, toxicity towards mites. It is possible that the levels of tartaric acid needed to coat bees with a toxic dose are higher than they are on a relatively smooth and barren toothpick. Toothpicks also attract watery compounds (hydrophilic) while bees are coated with oils and are hence more water-repellent (hydrophobic). Maybe the availability of tartaric acid on toothpicks is higher than it would be on oilier bee bodies. Formic acid also worked much better on the wood surface than on bees, an intriguing insight for a well-used and effective mite control. Formic acid is also known to be directly toxic to mites and their cells, and the authors make clear that both direct toxicity and grippiness are clear and perhaps synergistic targets for mite control. The widely used miticide oxalic acid also wins by being directly toxic to mites at levels that are relatively safe for bees, demonstrating that there are many possible ways to turn organic acids into effective treatments.

Lactic acid came out as the best candidate in the study group for divorcing mites from their bees. This acid worked well at dislodging mites from both toothpicks and bees. Lactic acid does not appear to be highly toxic to mites and instead seems to act by changing the mechanics of hanging on. This is a nice lead for exploring acids with similar qualities for their abilities to both grease the ‘Rotavar’ and make bees a more slippery host. In another intriguing result from this nice study, mites that simply walked across paper holding lactic acid were then less good in future grip tests. What is it about lactic acid that burns, cleans or otherwise insults the complex and surprisingly ‘soft’ tarsi of mites?

If this topic has gripped you, consider reading up on the field thanks to a recent open-access paper on stickiness by graduate student Luc van den Boogaart and colleagues in the Netherlands (van den Boogaart, L.M.; Langowski, J.K.A.; Amador, G.J. Studying Stickiness: Methods, Trade-Offs, and Perspectives in Measuring Reversible Biological Adhesion and Friction. Biomimetics 2022, 7, 134; https://www.mdpi.com/2313-7673/7/3/134). For those of us who have stored ‘Freshman Physics’ in a remote hard drive, they give a clear review of how these forces work across organisms; in their words ‘from ticks to tree frogs’. Maybe their figures and insights will inspire a beekeeper or scientist to dream up a safe, effective route to dislodge mites from bees and prevent them from climbing back on. Pulling in people with a knowledge of physics, or just really good imaginations and the ability to build and deploy Rotavars (imagine how entertaining those can be, a la squirrel spinners… https://www.youtube.com/shorts/nBKb_z4_tGY), can only help in the hunt for new mite controls and healthier bees.

]]>By: Nina Bagley

Miss Lillian Love was born into a Quaker family in Marion, Indiana on October 24, 1880. Her family was from Decatur, Indiana. Her father, Granville Love, was born in Indiana. In 1860, he married Nancy J. Gillibrand. Her family came from England and settled in the vicinity of Indianapolis. The two were married on August 11, 1868, in Morgan County, Indiana. Granville was a farmer and ran a huckster wagon, which proved a good business. Mrs. Nancy Love had nine children from 1869 to 1892. She died on January 31, 1936, at eighty-six, in Decatur, Indiana. Lillian’s father, Granville Love, died May 7, 1925, in Guilford, Indiana. All the children would be trained in English and piano at Central Normal College in Danville, Indiana.

Miss Lillian Love was born into a Quaker family in Marion, Indiana on October 24, 1880. Her family was from Decatur, Indiana. Her father, Granville Love, was born in Indiana. In 1860, he married Nancy J. Gillibrand. Her family came from England and settled in the vicinity of Indianapolis. The two were married on August 11, 1868, in Morgan County, Indiana. Granville was a farmer and ran a huckster wagon, which proved a good business. Mrs. Nancy Love had nine children from 1869 to 1892. She died on January 31, 1936, at eighty-six, in Decatur, Indiana. Lillian’s father, Granville Love, died May 7, 1925, in Guilford, Indiana. All the children would be trained in English and piano at Central Normal College in Danville, Indiana.

Lillian’s parents, Granville and Nancy Love.

Lillian had two years of college, became a teacher, and taught in Indiana and Florida. Women still couldn’t find jobs other than teaching. Lillian and her youngest sister Flossie were involved in women’s rights and equal opportunity for women; they supported women’s rights to vote.

In 1904, Lillian moved to Tacoma, Washington, where she taught for several years. Finding her husband in 1907, she married Jay Levant Hill, who was twenty-five years older than her. Lillian’s husband, Jay, was an inventor who owned his own lumber business. Lillian said that her husband’s “brain was mechanically bent.”

Miss Lillian Love, taken in Washington State prior to her marriage to J. Levant Hill.

Their home would be Mount Shadow Ranch, a two-hundred-acre farm with a charming yellow California-style bungalow, two and a half miles from Elbe, Washington. Surrounding the farm were the bee’s favorite purple hills of fireweed.

Fireweed is a plant that enjoys cool and moist climates and thrives in Pacific Northwest forestlands. It is also considered one of the most prolific plants for honey production, with its nectar having a high sugar concentration. It has a “lightly spicy” or “buttery” flavor.

If you shut your eyes and listen, you can hear the train whistle in the distance as it stops at Park Junction Station in the middle of Mount Shadow Ranch.

1926 – Lillian Hill at Mt. Rainier

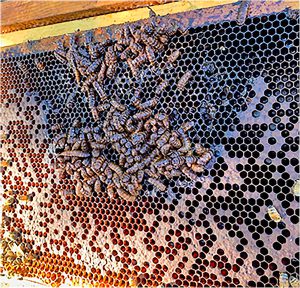

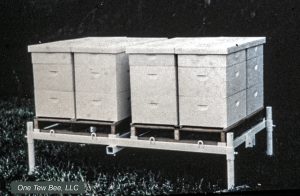

Apiary. Image featured in American Bee Journal

“We have some thirty acres under cultivation,” said Mrs. Hill; The rest of the farm is logged-off land which we use to pasture our herd of fifty cattle.”

—American Bee Journal, April 1926.

One day in 1913, an old man came peddling bees. “You have a wonderful place here for bees,” he said, convincing Mrs. Hill to invest in six swarms. Before the older man came along, she had never seen a swarm of bees before. Her six swarms increased and produced so much honey that in 1914 Lillian Hill invested in twenty more swarms, giving her forty hives. That year she harvested 6,500 pounds of pure honey. Lillian had an entrepreneurial spirit and determination to succeed in a male-dominated industry.

Lillian’s marriage to J. Hill.

I don’t know how she accomplished so much. Mrs. Lillian Hill kept a tidy home, raised beef cattle, Duroc-Jersey hogs, geese and ducks, and grew vegetables in the garden. But it would be the bees she loved the most!

Lillian was part owner of the Ranch and owner of the Mount Shadow Apiary. She had a gentle personality. She was independent and had a fire in her eyes that you could see demanded respect.

Being a novice beekeeper found her unprepared. In 1915, she encountered her first obstacle, European Foulbrood that would bring havoc to her beeyard. Words that no beekeeper wanted to hear or experience, the only cure, the dreadful burning of the hives. After that horrible experience with “American Foulbrood,” she only kept a dozen colonies of bees providing honey for her family and neighbors. (American Bee Journal, April 1926.)

“I never camp,” confessed Lillian Hill. “On either the trail of my successes or my failures. I go right on.” That’s her philosophy in a nut-shell.

Although childless, she cared for the children from reform schools, orphan asylums or neighboring farms; she taught the boys and girls everything about beekeeping so they could pay their way through school. She believed that the best and safest way to help any human being is to help him help himself. Particularly, those who needed guidance and education.

In the 1900s, the U.S. was a diverse nation, and its children lived in various circumstances. For years, she had been the leader of the Boys’ and Girls’ Bee Club of Elbe. One of her boys won nearly $80.00 with his exhibits of bees and honey at the Western Washington Fair.

Lillian increased her hives to twenty-six to help one of her boys and it didn’t stop there!

In 1924, to help one of her girls through school, she invested in thirty more hives and loaned them to the girl. The girl lived next door to an abandoned schoolhouse on an acre of ground, which got Mrs. Hill thinking, “I could rent the schoolhouse and land from the school board.”

1921 – Freddie May with his siblings before they were placed in the Washington Children’s Home.

One day in 1924, a young man showed up at the Ranch. His name was Freddie May, and he was born in 1912 in Denver, Colorado. When he was eight years old, he lived in Wenatchee, Washington. His father abandoned the family, and their mother could not care for six children. The children were placed in the Washington Children’s Home in Wenatchee, Washington, in 1921.

Mount Rainier Apiary. Freddie May and Mrs. Lillian Hill.

Freddie somehow got his hands on a newspaper. He came across the ad for a permanent position in beekeeping work. Freddie wanted to learn about the beekeeping business under the leadership of Mrs. Lillian Hill, so he rode on “a bicycle” from Wenatchee, Washington to Elbe, Washington, a hundred and ninety five miles! He was energetic and full of fire and wanted to learn beekeeping.

Lillian took a liking to Freddie and wanted to help him make money to pay his way through school, so she furnished Freddie with plenty of bees on a commission basis of fifty-fifty. In four months, the Colorado cyclist made five hundred dollars for himself.

Freddie would consider Mrs. Lillian Hill his mother and next of kin. Lillian and her husband would become Freddie’s foster parents giving him a home with security. He would attend Eatonville High School and work on the Ranch. He would continue beekeeping and eventually marry and have a family.

During the season of 1925, Mrs. Hill was able to establish the Colorado youth in the schoolhouse helping young boys and girls in need teaching them beekeeping.

In 1926, Lillian Hill had over one hundred and fifty hives of Italian bees, eighty-five at the schoolhouse and sixty-five at home. She produced at least 10,000 sections of comb honey. Mrs. Hill would advertise in the newspapers to get workers “Wanted – an experienced farmer for a permanent position.”

Most of the marketing she did herself in her Buick car. She supplied the best stores in Tacoma and Seattle. “I don’t have to hunt for a market,” declared this energetic woman. In one year, Mrs. Hill raised sixty queens. That was the part of her business that she enjoyed most of all. Mrs. Hill was the president of the Pierce County Beekeepers’ Association for two years.

Mount Rainier

Both triumphs and disasters have knocked often at Lillian Hill’s door on the Mount Shadow Ranch, but neither one ever fazed her. This woman had grit and plenty of it!

Around 1927, Freddie would accidentally run over Lillian’s foot crushing it while she was teaching him how to drive the tractor. An unfortunate outcome was that the doctors had to amputate her leg due to blood poisoning. Lillian had a prosthetic leg from the knee down, but that didn’t stop her. She took it in stride and persevered. In 1929, unfortunately, her husband died. He was the youngest of five and the last of his siblings. He was seventy-one years old. I will say some lives have more trial or tribulations than others, to be sure, but no life is without events that test and challenge us.

In the 1930 census, Lillian is listed as a widow forty-nine years old, with fifty men aged eighteen to sixty-six listed as boarders at the Mount Shadow Ranch and working for Lillian Hill. That’s a lot of men to manage. You would have to have grit and be firm! Among the fifty men working on the farm was Freddie May, the youngest, who was eighteen. His occupation was a Logger.

Not being able to care for the Ranch and losing her husband, not to mention the tractor accident, left her feeling like it would be time to sell the Ranch. Lillian Hill would place the Ranch up for sale.

Advertised in the Tacoma Daily Ledger Sunday, June 23, 1929. “Mountain Shadow Ranch. It is one of the best-stocked Dairy Farms in western Washington, with running water in every field and excellent soil. Forty acres cleared; 120 acres fenced for hogs and cattle; stocked and making money; good seven-room house with school buses to Elbe and Eatonville high school. The farm is a must-see to appreciate it. We will consider small trade—a price of $15,000. Write to Lillian L. Hill for an appointment.”

Family photo of Albert Cook, first wife Nora and their children.

Lillian’s family Bible.

A lot happened in 1930. The Ranch sold, and Lillian Hill married Albert Cook, a widower who worked in the lumber industry. His wife Nora passed away in March of 1929 at the age of fifty-one; they had six children together. Lillian didn’t mind an extended family. She was raising her niece Esther who she adopted at a young age and her foster son Freddie May. After all, Lillian loved children and teaching. Her first husband was in the lumber business so she probably knew Albert Cook.

Albert would marry Lillian in 1930, build apartment buildings and retire from the lumber industry. The two would live in Tacoma, Washington. Lillian’s beekeeping days came to an end, her new occupation would be owner and landlord of her apartment buildings.

Lillian had a very loving relationship for nineteen years with her husband Albert. In May of 1949, Albert passed away at the age of seventy-three. He was buried beside his first wife, Nora, in Tacoma, Pierce, Washington.

The income from the apartments and other investments would give Lillian a comfortable life for the next sixteen years. She lived to be eighty-eight and passed away August 19, 1969 in Tacoma, Pierce, Washington Lillian was a Sixth Avenue Baptist church member. She was buried next to her first husband, Jay Levant Hill.

Freddie May lived to be eighty-three years old. Freddie kept his surname May. He went by Fred (Cook) May, Sr. “Commander” as best by everyone who loved him.

Lillian in her sister Flossie’s backyard. Her dress is purple and black print. She and her sister Flossie always had a matching rhinestone necklace.

Lillian’s youngest sister Flossie, who she remained close with, lived in California. Flossie had a granddaughter Karla who enjoyed her aunt Lillian’s visits. She remembers sitting on her grandmother’s hunter green “davenport” with her aunt Lillian. Her grandma Flossie would sit in her desk chair across the room and the two sisters would talk for hours.

Lillian’s great-niece Karla also remembers how “intriguing” her aunt was. Lillian had blue eyes, was fair-haired and had rosy cheeks. She wore her hair in a braid reaching her waist until one day; she cut it off, curled it up, and put it in a small box for keeping. Karla remembers her Aunt Lillian as sweet but at the same time, tough and gutsy!

Marcus Aurelius was a stoic philosopher. His quote reminded me of Mrs. Lillian Love, her struggles as a woman in the 1900’s and how she put others before her, passing her knowledge about beekeeping on to so many young boys and girls in need. I would like to thank Lillian’s great-niece Karla Babcock for sharing her memories of her Aunt Lillian and grandmother Flossie.

“A life of sacrifice and putting the well being collective first, just like the bees.”

—Marcus Aurelius

Ohioqueenbee

Nina M. Bagley

Columbus, Ohio.

Nestmate Recognition

Nestmate RecognitionBy: Clarence Collison

Pheromones are involved in intraspecific chemical communication; however, the glands associated with compounds used in nestmate recognition in honey bees remain elusive. This search is difficult since nestmate cues can arise from both within the colony, and from the environment (Kalmus and Ribbands, 1952). For example, Downs and Ratnieks (1999) found no evidence that honey bee guards used heritable cues; instead, guards appear to rely exclusively on environmental cues to distinguish nestmates from non-nestmates. However, nestmate cues can also be produced by the individual, and thus must be under genetic control (Breed, 1983; Page Jr. et al., 1991). A further factor is that the wax used to build comb in the colony is both produced and manipulated by the bees, which means it may be a medium into which recognition cues are transferred (Breed et al., 1998). Therefore, Breed et al. (1998) stated that no single factor is responsible for nestmate recognition in honey bees; rather, all three factors (genetically determined cuticular signatures, exposure to comb wax, and environmental cues e.g. floral cues) seem to work together (Martin et al., 2018).

Comb wax in honey bee colonies serves as a source and medium for transmission of recognition cues. Worker honey bees learn the identity of their primary nesting material, the wax comb, within an hour of emergence. In an olfactometer, bees discriminate between combs on the basis of odor; they prefer the odors of previously learned combs. Representatives of three of the most common compound classes in bee’s wax were surveyed for effects on nestmate discrimination behavior. Hexadecane, octadecane, tetracosanoic acid and methyl docosanoate make worker honey bees less acceptable to their untreated sisters. Other similar compounds did not have this effect. These findings support the hypothesis that nestmate recognition in honey bees is mediated by many different compounds, including some related to those found in comb wax (Breed and Stiller, 1992).

Breed et al. (1998) investigated how kin recognition cues develop and cue differentiation between honey bee colonies. Exposure to the wax comb in colonies is a critical component of the development of kin recognition cues. In this study, they determined how the cues develop under natural conditions (in swarms), whether the genetic source and age of the wax affect cue ontogeny, and whether exposure to wax, as in normal development, affects preferential feeding among bees within social groups. Cue development in swarms coincided with wax production, rather than with the presence of brood or the emergence of new workers; this finding supported previous observations concerning the importance of wax in cue ontogeny. Effective cue development required a match between the genetic source of the workers attempting to enter the hive, the wax to which they were exposed and the guards at the hive entrance. The wax must also have been exposed to the hive environment for some time. Cues gained from wax did not mask or override cues used in preferential feeding interactions; this finding supports the contention that two recognition systems, one for nestmate recognition and the other for intra-colonial recognition, are present.

Recognition of nestmates from aliens is based on olfactory cues, and many studies have demonstrated that such cues are contained within the lipid layer covering the insect cuticle. These lipids are usually a complex mixture of tens of compounds in which aliphatic hydrocarbons are generally the major components. Dani et al. (2005) tested whether artificial changes in the cuticular profile through supplementation of naturally occurring alkanes and alkenes in honey bees affect the behavior of nestmate guards. Compounds were applied to live foragers in microgram quantities and the bees returned to their hive entrance where the behavior of the guard bees was observed. In this fashion, they compared the effect of single alkenes with that of single alkanes; the effect of mixtures of alkenes versus that of mixtures of alkanes and the whole alkane fraction separated from the cuticular lipids versus the alkene fraction. With only one exception (the comparison between n-C19 and (Z)9-C19), in all the experiments bees treated with alkenes were attacked more intensively than bees treated with alkanes. This led them to conclude that modification of the natural chemical profile with the two different classes of compounds has a different effect on acceptance and suggests that this may correspond to a differential importance in the recognition signature.

Cuticular hydrocarbons (CHCs) function as recognition compounds in honey bees. It is not clearly understood where CHCs are stored in the honey bee. Martin et al. (2018) investigated the hydrocarbons and esters found in five major worker honey bee exocrine glands, at three different developmental stages (newly emerged, nurse and forager) using a high temperature GC analysis. They found the hypopharyngeal gland contained no hydrocarbons nor esters, and the thoracic salivary and mandibular glands only contained trace amounts of n-alkanes. However, the cephalic salivary gland (CSG) contained the greatest number and highest quantity of hydrocarbons relative to the five other glands with many of the hydrocarbons also found in the Dufour’s gland, but at much lower levels. They also discovered a series of oleic acid wax esters that lay beyond the detection of standard GC columns. As a bee’s activities changed, as it aged, the types of compounds detected in the CSG also changed. For example, newly emerged bees have predominately C19-C23n-alkanes, alkenes and methyl-branched compounds, whereas the nurses’ CSG had predominately C31:1 and C33:1 alkene isomers, which are replaced by a series of oleic acid wax esters in foragers. These changes in the CSG were mirrored by corresponding changes in the adults’ CHCs profile. The CSG is a major storage gland of CHCs. As the CSG duct opens into the buccal cavity (mouth), the hydrocarbons can be worked into the comb wax and could help explain the role of comb wax in nestmate recognition experiments.

Cuticular hydrocarbons (CHCs) function as recognition compounds in honey bees. It is not clearly understood where CHCs are stored in the honey bee. Martin et al. (2018) investigated the hydrocarbons and esters found in five major worker honey bee exocrine glands, at three different developmental stages (newly emerged, nurse and forager) using a high temperature GC analysis. They found the hypopharyngeal gland contained no hydrocarbons nor esters, and the thoracic salivary and mandibular glands only contained trace amounts of n-alkanes. However, the cephalic salivary gland (CSG) contained the greatest number and highest quantity of hydrocarbons relative to the five other glands with many of the hydrocarbons also found in the Dufour’s gland, but at much lower levels. They also discovered a series of oleic acid wax esters that lay beyond the detection of standard GC columns. As a bee’s activities changed, as it aged, the types of compounds detected in the CSG also changed. For example, newly emerged bees have predominately C19-C23n-alkanes, alkenes and methyl-branched compounds, whereas the nurses’ CSG had predominately C31:1 and C33:1 alkene isomers, which are replaced by a series of oleic acid wax esters in foragers. These changes in the CSG were mirrored by corresponding changes in the adults’ CHCs profile. The CSG is a major storage gland of CHCs. As the CSG duct opens into the buccal cavity (mouth), the hydrocarbons can be worked into the comb wax and could help explain the role of comb wax in nestmate recognition experiments.

Worker honey bees are able to discriminate between combs on the basis of genetic similarity to a learned comb. The nestmate recognition cues that they acquire from the comb also have a genetically correlated component. Cues are acquired from comb in very short exposure periods (five minutes or less) and can be transferred among bees that are in physical contact. Gas chromatographic analysis demonstrates that bees with exposure to comb have different chemical surface profiles than bees without such exposure. These results support the hypothesis that comb-derived recognition cues are highly important in honey bee nestmate recognition. These cues are at least in part derived from the wax itself, rather than from floral scents that have been absorbed by the wax (Breed et al., 1995).

Experiments indicated that the most important recognition pheromones are the fatty acids, particularly palmitic acid, palmitoleic acid, oleic acid, linoleic acid, linolenic acid and tetracosanoic acid. These fatty acids are mixed with the wax hydrocarbons from wax glands, molded into comb and then transferred onto the workers as they contact the comb. The result is a colony level signature that varies little among workers in a colony. Newly emerged workers have few external fatty acids or hydrocarbons. Oleic acid is more abundant than the other fatty acids on newly emerged bees, but the amount of oleic acid on the cuticle does not vary significantly among colonies. Newly emerged workers are accepted even though they have no signature yet; the “password” for new bees to be admitted to their colony is apparently the lack of a signal. This conclusion is corroborated by the finding that guards tend to treat sodium hydroxide-washed older bees as if they are newly emerged (Breed, 1998).

The integration of recognition cues is described as follows. Fatty acids and hydrocarbons are components of the wax comb that is produced by the bees. The relative abundances of fatty acids and hydrocarbons in wax varies among colonies, giving them unique chemical signatures. Food odors may also be absorbed by the comb, adding to its uniqueness. Newly emerged bees produce their own hydrocarbon coating, which is modified as they move around the nest by the addition of hydrocarbons and fatty acids from the comb. Of the compounds tested in the laboratory, fatty acids are the most important recognition pheromones, but other, as yet untested compounds may also contribute to the recognition odor. Hydrocarbons have generally been assumed to be the primary recognition pheromones of honey bees. However, none of the major structural hydrocarbons of honey bees (i.e., n-alkanes) yields a positive result in a recognition bioassay, nor do these compounds differ significantly in relative concentration among families of bees (Breed, 1998).

The environmental and genetic components of recognition are difficult to separate even in controlled conditions. Getz and Smith (1983) showed that the honey bee discriminates between full and half-sisters raised in the same hive, on the same brood comb in neighboring cells, thus demonstrating a significant genetic component to the recognition process.

Nestmate recognition information can come from either contact chemoreception or olfaction. Mann and Breed (1997) investigated what role airborne olfactory cues play in nestmate recognition by honey bee colony guards, and how do these signals affect guard orientation and behavior? They demonstrated that airborne cues play a significant role in guard bee recognition of nestmates and non-nestmates. Exposure of a guard bee to the scent of a non-nestmate resulted in increased locomotory rate and changes in the directional orientation of guard bees. Exposure to scent of a non-nestmate did not, however, increase the likelihood that a second non-nestmate would be attacked when placed with the guard. Observations of guard behavior at colony entrances indicate that guards discriminate nestmates from non-nestmates with high efficiency.

Floral oils are an important component of the honey bee’s olfactory environment. Bowden et al. (1998) used laboratory and field tests to determine whether floral oils affect nestmate recognition in honey bees. In the laboratory, newly emerged worker bees, that have not been exposed to comb wax, responded more aggressively to bees that had been exposed to floral oils than unexposed control bees. In the field, guard bees did not respond differently to foragers that had been exposed to floral oils. Floral oils may play a supplementary role in nestmate recognition; however, if they have any effect, it is secondary to cues acquired from comb during development.

Downs et al. (2000) investigated the effect that floral oils (anethole, citronellal, limonene and linalool) have on the probability of nestmates and non-nestmates being accepted by guard bees at nest entrances. Floral oils did not affect the probability of workers, either nestmates or non-nestmates, being accepted by guards. However, the presence of floral oils did increase the time taken for a guard to reject an introduced bee. These data show that guards are sensitive to floral oils but use other recognition cues when assessing colony affiliation.

Honey bees have the ability to distinguish among groups of larvae that are destined to become queens and preferentially rear highly related nestmate larvae over less related larvae that are not nestmates (Page and Erickson, 1984).

Colonies of honey bees from two patrilines (cordovan and dark) were established and observations were made on the behavior shown by the worker bees in rearing queen larvae within their colonies. The relationship among the bees within these colonies was either r = ¾ (super-sisters) or r = ¼ (half sisters). The worker bees showed preferential care to the queen larvae that were of their own patriline. Workers of the cordovan patriline showed a stronger preference for larvae of their own patriline than did the dark workers. Cordovan workers also showed a higher rate of visitation, indicating behavioral differences between the patrilines. These results suggest that kin selection is operating on honey bee behavior used in rearing reproduction (Noonan, 1986).

A honey bee queen is usually attacked if she is placed among the workers of a colony other than her own. This rejection occurs even if environmental sources of odor, such as food, water and genetic origin of the workers, are kept constant in laboratory conditions. The genetic similarity of queens determines how similar their recognition characteristics are; inbred sister queens were accepted in 35% of exchanges, outbred sister queens in 12% and non-sister queens in 0%. Carbon dioxide narcosis (stuper, unconsciousness) results in worker honey bees accepting non-nestmate queens. A learning curve is presented, showing the time after narcosis required by workers to learn to recognize a new queen. In contrast, workers transfer results in only a small percentage of the workers being rejected. The reason for the difference between queens and workers may be because of worker and queen recognition cues having different sources (Breed, 1981).

Boch and Morse (1974, 1979) have shown that honey bee queens can be recognized individually by swarms of bees. They found that marking a queen with shellac-based paint to give her a distinctive odor resulted in workers later exhibiting a preference for any queen marked with that paint. However, their experiments do not show whether the odors used by workers to recognize queens are produced by the queens or are environmentally acquired. In a series of studies concerned with queen introduction into colonies, Szabo (1974, 1977) also found that workers could discriminate among queens, but did not approach the issue of the source of recognition odors directly. It was also found that factors such as the age and weight of an introduced queen could affect worker choice among introduced queens. Yadava and Smith (1971) found that the mandibular gland contents of the queen were important in the release of worker aggression towards an introduced queen (Breed, 1981).

References

Boch, R. and R.A. Morse 1974. Discrimination of familiar and foreign queens by honey bee swarms. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 67: 709-711.

Boch, R. and R.A. Morse 1979. Individual recognition of queens by honey bee swarms. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 72: 51-53.

Bowden, R.M., S. Williamson and M.D. Breed 1998. Floral oils: their effect on nestmate recognition in the honey bee, Apis mellifera. Insectes Soc. 45: 209-214.

Breed, M.D. 1981. Individual recognition and learning of queen odors by worker honey bees. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 78: 2635-2637.

Breed, M.D. 1983. Nestmate recognition in honey bees. Anim. Behav. 31: 86-91.

Breed, M.D. 1998. Recognition pheromones of the honey bee. Bioscience 48: 463-470.

Breed, M.D. and T.M. Stiller 1992. Honey bee, Apis mellifera, nestmate discrimination: hydrocarbon effects and the evolutionary implications of comb choice. Anim. Behav. 43: 875-883.

Breed, M.D., M.F. Garry, A.N. Pearce, B.E. Hibbard, L.B. Biostad and R.E. Page, Jr. 1995. The role of wax comb in honey bee nestmate recognition. Anim. Behav. 50: 489-496.

Breed, M.D., E.A. Leger, A.N. Pearce, and Y.J. Wang 1998. Comb wax effects on the ontogeny of honey bee nestmate recognition. Anim. Behav. 55:13-20.

Dani, F.R., G.R. Jones, S. Corsi, R. Beard, D. Pradella and S. Turillazzi 2005. Nestmate recognition cues in the honey bee: differential importance of cuticular alkanes and alkenes. Chem. Senses 30: 477-489.

Downs, S.G. and F.L.W. Ratnieks 1999. Recognition of conspecifics by honey bee guards (Apis mellifera) uses non-heritable cues applied to the adult stage. Anim. Behav. 58: 643-648.

Downs, S.G., F.L.W. Ratnieks, S.L. Jefferies, and H.E. Rigby 2000. The role of floral oils in the nestmate recognition system of honey bees (Apis mellifera L.). Apidologie 31: 357-365.

Getz, W.M. and K.B. Smith 1983. Genetic kin recognition: honey bees discriminate between full and half sisters. Nature 302: 147-148.

Kalmus, H. and C.R. Ribbands 1952. The origin of the odours by which honey bees distinguish their companions. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 140: 50-59.

Mann, C.A. and M.D. Breed 1997. Olfaction in guard honey bee responses to non-nestmates. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 90: 844-847.

Martin, S.J., M.E. Correia-Oliveira, S. Shemilt, and F.P. Drijfhout 2018. Is the salivary gland associated with the honey bee recognition compounds in worker honey bees (Apis mellifera)? J. Chem. Ecol. 44: 650-657.

Noonan, K.C. 1986. Recognition of queen larvae by worker honey bees (Apis mellifera). Ethology 73: 295-306.

Page, R.E. Jr. and E.H. Erickson Jr. 1984. Selective rearing of queens by worker honey bees: kin or nestmate recognition. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 77: 578-580.

Page, R.E. Jr., R.A. Metcalf, R.I. Metcalf, E.H. Erickson Jr. and R.L. Lampman 1991. Extractable hydrocarbons and kin recognition in honey bee (Apis mellifera L.). J. Chem. Ecol. 17: 745-756.

Szabo, T.I. 1974. Behavioural studies of queen introduction in the honey bee 2. Effect of age and storage conditions of virgin queens on their attractiveness to workers. J. Apic. Res. 13: 127-135.

Szabo, T.I. 1977. Behavioural studies of queen introduction in the honey bee 6. Multiple queen introduction. J. Apic. Res. 16: 65-83.

Yadava, R.R.S. and M.V. Smith 1971. Aggressive behavior of Apis mellifera L. workers towards introduced queens II. Role of mandibular gland contents of the queen in releasing aggressive behavior. Cand. J. Zool. 49: 1179-1183.

Clarence Collison is an Emeritus Professor of Entomology and Department Head Emeritus of Entomology and Plant Pathology at Mississippi State University, Mississippi State, MS.

]]>

The BIP team takes a break from inspecting colonies. From left to right: Eric Malcolm, Ben Sallmann, Cade Houston, Anne Marie Fauvel. © 2022, Eric Malcolm, beeinformed.org

Looking for something to do Thursday, Sept. 14? Want to support BIP?

Looking for something to do Thursday, Sept. 14? Want to support BIP?

Join BIP LIVE for an hour of enjoyable conversation with beekeeping YouTuber David Burns! He, alongside Bee Informed Partnership’s Anne Marie Fauvel and Eric Malcolm, will discuss what BIP is all about and chat about honey bee health.

David is sponsoring this livestream fundraising event as an opportunity to share more about BIP’s work with the community and help raise much-needed funds to support their mission.

Stop by for a visit and stay for the fun by visiting David Burns’ YouTube channel on Thursday, September 14 at 8pm EST / 7pm CST!

YouTube link not working? Copy and paste this link into your browser’s search bar instead: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8nCvJNSE_JY

Did you know David Burns writes an article in Bee Culture every month? Check out his article from June and then subscribe to never miss one of his article! June article: https://www.beeculture.com/hot-hive-inspections/

]]>Click Here if you listened. We’re trying to gauge interest so only one question is required; however, there is a spot for feedback!

Read along below!

My Apiary Ecosystem

My Apiary Ecosystem

Honey bees are only a part of it.

By: James E. Tew

There’s always going to be something

In my hives or in my life, there is always going to be something – some issue or some problem. I literally just finished a phone call with one of my adult daughters. She had just eliminated a harmless Wolf Spider (Tigrosa annexa) because it frightened her young son (my nine-year old grandson). A few weeks ago, she had a problem with ants in her kitchen, but now they are gone. Now, she has Springtails (Collembola) in one of her bath showers. She complained to me that she feels that her home is under constant attack. I tried to tell her that there is always going to be something going awry. Always. Chill out. I don’t think she listened to me, but I listened to her.

Since I have spent my adult life studying honey bees, she assumed that I was also an information resource for Springtails. Readers, I don’t know anything about these small flea-sized arthropods, but unintentionally, my daughter set me to thinking and exploring. What do I know about Springtails? In all my beekeeping years, I have never asked or thought about the presence of Collembola in bee hives.

Figure 1. Springtails are about the size of a flea and seemingly cause no harm to bees or beekeeping.

Springtails are common in organic materials that are being degraded. On a whim, I keyed in a web search on Springtails (Collembola) in bee hives. I immediately got hits. All the citations that I found were from observant beekeepers. Having not found any information from academic or regulatory sources, I went to an AI open-source app and was given the following, undocumented information.

Collembola, commonly known as Springtails, are small arthropods that belong to the class Collembola. They are found in a wide range of habitats, including soil, leaf litter and decaying organic matter. While they are not typically associated with bee hives, it is possible for Springtails to be present in bee hives under certain conditions.

Springtails are detritivores, meaning they feed on decaying organic matter and microorganisms. In a bee hive, there may be small amounts of organic debris, such as pollen, beeswax and other residue, which could provide a food source for Springtails. However, the presence of Springtails in a bee hive is usually considered incidental and not a significant problem for honey bees.

I had no idea

I had no idea that these small animals could occasionally be found in hives, but my conversation with my daughter came at a time that I had been pondering this very concept. What is routinely in my bee hives and in my apiary other than honey bees? I have never found a comprehensive listing of the lifeforms that I could expect to find there.

Figure 2. Fire ants and my honey bees. Do the ants help or hurt my bees? Ants, of many species, are common in my beeyard.

My apiary is essentially a distinct ecosystem. My apiary is where I keep my bees, but I have long since realized that many other species find that an apiary is home for them, too. These “unknowns” can apparently fall into three broad categories: harmful, beneficial or neutral.

The Big List

Early in our beekeeping journeys, we are exposed to what I have named the “Big List.” Some of the common entries on this list are raccoons, skunks, ants, wax moths, small hive beetles, birds, toads and mice. It is not my intent to discuss these common hive intruders here. Yet, in the hours and hours that I have either sat by my colonies or pawed through them, I routinely see other species and wonder what they’re up to as they bum around my hives. Usually, their presence remains a mystery.

Flies

Of course, there are numerous species of flies in and around my hives and colonies. We’ve all seen them. In fact, the classic book, Honey Bee Pests, Predators, & Diseases (Morse, Roger A. & Kim Flottum. Honey Bee pests, Predators, & Diseases. A.I.Root Company, Medina, Ohio. 44691. 718 pp. Chpt 8. P 143-162.) has a designated chapter on various fly species and their effects on bee colonies. Essentially, flies and their associated larvae are degraders and generally, do not have a harmful effect on healthy bees.

Figure 3. Common Green Bottle Fly (Blow Fly), probably Lucilia sericata, parked on the front of one of my active hives.

But, I can’t help but notice the occasional Green Bottle Fly nosing around my active hives. They are very flighty and will not allow a close camera shot before taking quick flight. Why are they there? I never see them get inside the hive.

Figure 4. Black Soldier Fly larvae, H. illucens larvae, on honey bee frame. (Scott Razee photo)

But there are unique encounters between various Dipterous species and honey bees that are rare. Anthony (Auth, C. Anthony, Hauser, M. & Hopkins, B.K. A scientific note on a black soldier fly (Stratiomyidae: Hermetia illucens) infestation within a western honey bee (Apis mellifera) colony. Apidologie 52, 576–579 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-021-00844-y) published a scientific note on a Black Soldier Fly (Stratiomyidae: Hermetia illucens) infestation within a western honey bee (Apis mellifera) colony. In the article abstract, Anthony, et al. reported:

Black soldier Fly larvae (Hermetia illucens) were discovered in a weak honey bee colony in Hailey, Idaho. The larvae were localized to the brood area and caused the affected comb to putrefy. Further communication with the beekeeper revealed that the colony recently returned from California and that the larvae likely originated there as well. In California, H. illucens are common and exist sympatrically with honey bees, yet there have been very few reports of damage. We therefore believe H. illucens are unlikely to cause damage to healthy colonies or significantly impact the apiculture industry. This report is the first published observation of H. illucens in Idaho and shows conclusively for the first time that H. illucens associates with honey bee colonies in North America.

Figure 5. Adult Black Soldier Fly (Utah State University Extension)

There are distinct Diptera species that either are outright harmful to bees or other flies that are considered to be minor pests. Examples of damaging species are Phorid Flies (Zombie Flies) while a lesser pest is the bee louse (Braula caeca). These pests are documented elsewhere in the beekeeping literature. I will not cover them here.

Earwigs

Figure 6. Adult European earwigs on the inner cover of my hive.

How bad can earwigs be? In Alabama, earwigs are commonly found in honey bee colonies in significant numbers. No doubt they are found in other states. I have noted that earwigs were not a common hive resident in Ohio, but that all changed a few years ago. I now have earwigs in my office, in my home and in my bee hives.

I don’t know that they do anything within the hive. I faintly remember one Russian paper, that reported that earwigs could be alternate hosts for the bacteria causing European Foulbrood. Other than that one point, I have never heard complaints about them.

Of course, they are a pain when extracting and must be caught in the filter when processing honey. Straining bees and bee parts from honey is bad enough, but earwigs in the honey filter are unsightly. I don’t know of anything that you can do about them. In fact, I’m not sure anything should be done about them.

Roaches

As an entomologist, I respect roaches. They are the consummate survivor. Obnoxious that they are to humans, one must respect their persistence. Many, many developmental years ago, roaches “learned” to fold their wings over their bodies so they could exploit more niches, than say, a broad-winged insect like a dragonfly (dragonflies will also occasionally prey on honey bees). By storing their folded wings over their bodies, cockroaches could, more easily, get under your refrigerator or inside your bee hives. They have been a challenge for me everywhere I have kept bees.

Like so many other insect visitors/invaders, roaches are drawn to both the sweet food supply as well as the protein supplies – and then there are all the decaying larvae and adult bees to munch on. The question is begged, “Why would roaches NOT be in our hives and stored equipment?”

In the beekeeping literature, it is often written that the damage roaches do is minimal, but I want to loudly say that the appearance of just a single roach in your honey house can dissuade even the staunchest customer who is considering buying your honey. And then there is the excreta to consider. In fact, one of my most serious concerns of both cockroaches and earwigs is the excrement that they leave behind.

Figure 7. Unfortunately, a cockroach is not an uncommon hive visitor.

It is also commonly written that cockroaches are primarily found in weakened or otherwise ailing colonies. Yes, that is surely true, but I will loudly say that great numbers of roaches happily live on the inner cover of populous colonies. When the outer cover is removed, in a flash, they scamper down into the bees.

In my opinion, there is little to be done to control a roach infestation. Protecting the customer and protecting the purity of the honey product is about all that can be done. Yet, I cannot conclusively say that a modest roach infestation is absolutely harmful to the bees. Maybe future studies will continue to add information to this colony co-habitant.

Honey Bee Cousins

Figure 8. A yellowjacket lunching on one of my dead honey bees.

Yellowjackets

Though yellowjackets are on my “Big List” and are common pests in the beeyard, I have included them here. In my yards, these brightly colored insects could almost be a traditional resident of my apiary. Yellowjackets get included on my “mystery” list due to technicalities.

Yellowjackets (probably Vespula maculifrons) readily see their honey bee cousins as a potential food supply. On occasion, these wasps may have a nest in my apiary, but much more likely is that these hymenopterous insects are simply foraging within my apiary.

Experienced beekeepers have commonly seen yellowjackets mulling around the detritus at the hive entrance, but they will also enter a weakened colony and take honey, pollen, brood and adults depending on their own colony needs.

As such, yellowjackets get an entry on the common list of bee colony pests, but they do not seem to be the effective cause of the colony’s decline but are more commonly responding to a colony that has been weakened by other factors. Yellowjackets can be numerous when robbing behavior is rampant.

Figure 9. Bumblebees can frequently be seen attempting to enter a honey bee colony. This can be disastrous for the bumblebee with deadly results.

Bumblebees

I frequently see bumblebees trying to enter a bee colony. How suicidal is that? Only on a few occasions have I stumbled onto a bumble nest in unused honey bee equipment, but they are frequently in my apiary surely searching for food.

In fact, bumblebees may not necessarily be attracted to my honey bee colonies specifically, but they may be drawn to certain characteristics or resources associated with honey bee colonies. I can come up with a few reasons that may explain why bumblebees are sometimes found near my honey bee colonies:

- Floral resources: Honey bee colonies are known to forage on a wide variety of flowering plants to collect nectar and pollen. Bumblebees, like honey bees, are also generalist foragers and seek out similar floral resources.

- Odor cues: Honey bee colonies emit a combination of pheromones and odors that can be detected by other bees, including bumblebees. These chemical signals may serve as attractants, potentially drawing bumblebees to the entrance of the honey bee colony.

- Nesting opportunities: While honey bees typically nest in enclosed structures such as beehives or tree cavities, bumblebees often create nests in the ground or other protected locations. However, bumblebees may occasionally take advantage of abandoned honey bee hives or other suitable cavities near a honey bee colony, which could lead to their presence in the area.

Figure 10. The apiary ecosystem can become complicated. This mantis is eating a yellowjacket that it caught while sitting atop one of my hives.

It’s important to note that interactions between bumblebees and honey bees can vary depending on the specific circumstances and the behavior of individual bees. While they may coexist peacefully in some cases, competition for limited resources, like nectar or nesting sites, can also occur.

My core point for this article